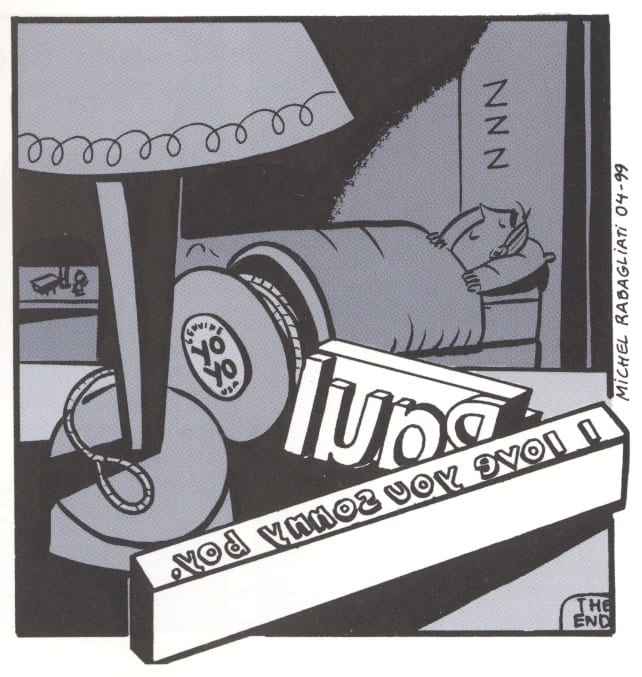

I’ve been reading Michel Rabagliati’s comics since the beginning of his career. My first Rabagliati story was “Paul, Apprentice Typographer” (2000), his second-ever comic, and a look at the final panel of “Typographer” will unlock some of the feelings, past and present, I’ve had about his work. The panel:

This is a gentle conclusion to a gentle story. In “Typographer,” Paul (a teenage Rabagliati in all but name) is picked up from accordion practice by his father, who then takes Paul out to lunch. After eating, Paul and Dad visit the typography shop where his father works, and Dad gives Paul informal lessons on how to operate various printing devices. Dad uses the Linotype machine to make two metal rows of text—with words arranged in reverse order, to print correctly when applied to paper—as gifts for his son. Then, while his father works a bit, Paul explores the shop on his own. He looks at one of his boogers under a loupe, and finds pictures of naked women on the bathroom walls. Then father and son go home. In the final panel, Paul falls asleep, and we see the two Linotype rows on his night table; we’ve seen the “Paul” one earlier in the story, but “I love you sonny boy” is new to us, and provides a sweet coda to “Typographer.”

I read “Typographer” when it was first published in English in Drawn and Quarterly 3 (2000), and for a time it shaped, and distorted, my opinion of Rabagliati’s art. Initially, I found the “sonny boy” conclusion too treacly. I expected my alternative comics to be sardonic and detached rather than sentimental. (Since then, my definition of alt-comix has grown beyond hipster irony, and I realize that “Typographer” was a perfect lead-in to the reprinted Sunday pages of Frank King’s Gasoline Alley in that issue of D and Q—Paul and his Dad have an idealized father-son relationship, as do Walt and Skeezix.) Also, I was bothered by Rabagliati’s drawing style. The proportions of the lamp seemed (and still seem) off-kilter, as if the lamp had previously belonged to Dr. Caligari, and I found Paul’s face in this panel (and throughout the story) too cartoony and exaggerated. I didn’t give up on Rabagliati’s comics, though; as English translations became available, I read Paul in the Country (2000), Paul Has a Summer Job (2002), Paul Moves Out (2005), Paul Goes Fishing (2008) and The Song of Roland (2012), and enjoyed them all, but I couldn’t shake my suspicion that Rabagliati’s art was too emotionally and visually simple.

Recently, after hearing that a new Paul book was on the way (Paul Joins the Scouts, forthcoming in English from Conundrum), I re-read all of Rabagliati’s books, and liked them much more. Optimism and simplicity do characterize his comics, but I discovered complexities there too, especially when I traced connections among the various books. Although each graphic novel stands alone, the entire Paul project is Rabagliati’s ongoing, thinly fictionalized autobiography, with each book focused on a particular period in his life. The Paul books all share the same chronology and many of the same characters, and across multiple volumes Rabagliati’s autobiography gradually assumes a greater density, closer to that of life itself. I’ll explore this density by talking about the organization of one individual Paul novel, Paul Goes Fishing, before sticking my toe into the deeper sea of networked motifs and narrative strategies in the series as a whole.

Fishing is a self-contained graphic novel with a conventional dramatic arc. Like all of Rabagliati’s books, it’s a satisfying read even for people unacquainted with the rest of Paul. One reason Fishing stands alone is Rabagliati’s use of narrative bookends. The first page of Fishing poses a mystery—a priest finds an enigmatic note with the money in his church’s collection boxes—but we don’t read the note, or understand its significance, until the end of the book. The mystery helps to bring the story to a conclusion by connecting back to the beginning.

A more subtle bookend involves the characters France and Peter. On page five of Fishing, Paul and his partner Lucie arrive at the opulent home of their friends France and Peter for a dinner party, which leads Rabagliati/Paul to muse on the many ways Peter is superior to Paul (he’s taller, he’s more ambitious and successful, he owns a spectacular wine collection, etc.). The dinner party winds down as the four discuss baby names; France is six months pregnant, and Lucie three. France and Peter don’t reappear, however, until much later in the book, after Lucie has a miscarriage, and after fourteen months (July 1991 to September 1992) have passed in the lives of the characters. Paul, Lucie, France, and Peter are on a picnic—having another meal together—and all play with France and Peter’s daughter Jeanne, who was named at that earlier dinner party. These scenes are similar, but with a key difference: the picnic scene reverberates with the sorrow Lucie and Paul feel over losing their baby.

After the picnic scene (and after captions that push the narrative months into the future), Lucie has another miscarriage, and she and Paul visit a fertility doctor for tests and treatment. By herself, France appears one more time in Fishing, when she offers ominous information over the phone about the hormones Lucie takes as part of the doctor’s regimen (171). Then France and Peter vanish from the story, as Rabagliati zeroes in on the two main characters and their final try at becoming parents. Throughout Fishing, France and Peter are aspirational yet troubling role models—Peter is more of an alpha male than Paul, Lucie wishes that she could have a successful pregnancy like France—but it’s only after Lucie and Paul stop comparing themselves to their friends, and take action to confront their specific fertility problems, that they are able to have a daughter. The final section of Fishing breaks out of the France-Peter bookend and charts a new direction for Paul and Lucie.

Another way Rabagliati brings unity to Fishing is by repeating motifs across the arc of his narrative. One such motif is the symbol of the vacuum cleaner, first seen on page 17 as Lucie tidies up the apartment before her parents visit. That night, Lucie dreams of both France and the vacuum cleaner:

This scene mixes dream-like non sequiturs (such as the store names on the apartment wall, and France’s Montreal Expos uniform) with potent meaning: the vacuum swallowing the baby’s pajama foreshadows the two Dilation and Curettage (“D & C”) procedures—basically a vacuuming-out of a womb to remove a dead fetus—that Lucie endures later in the story. During her first D & C, Lucie even whispers “The vacuum cleaner…” (148).

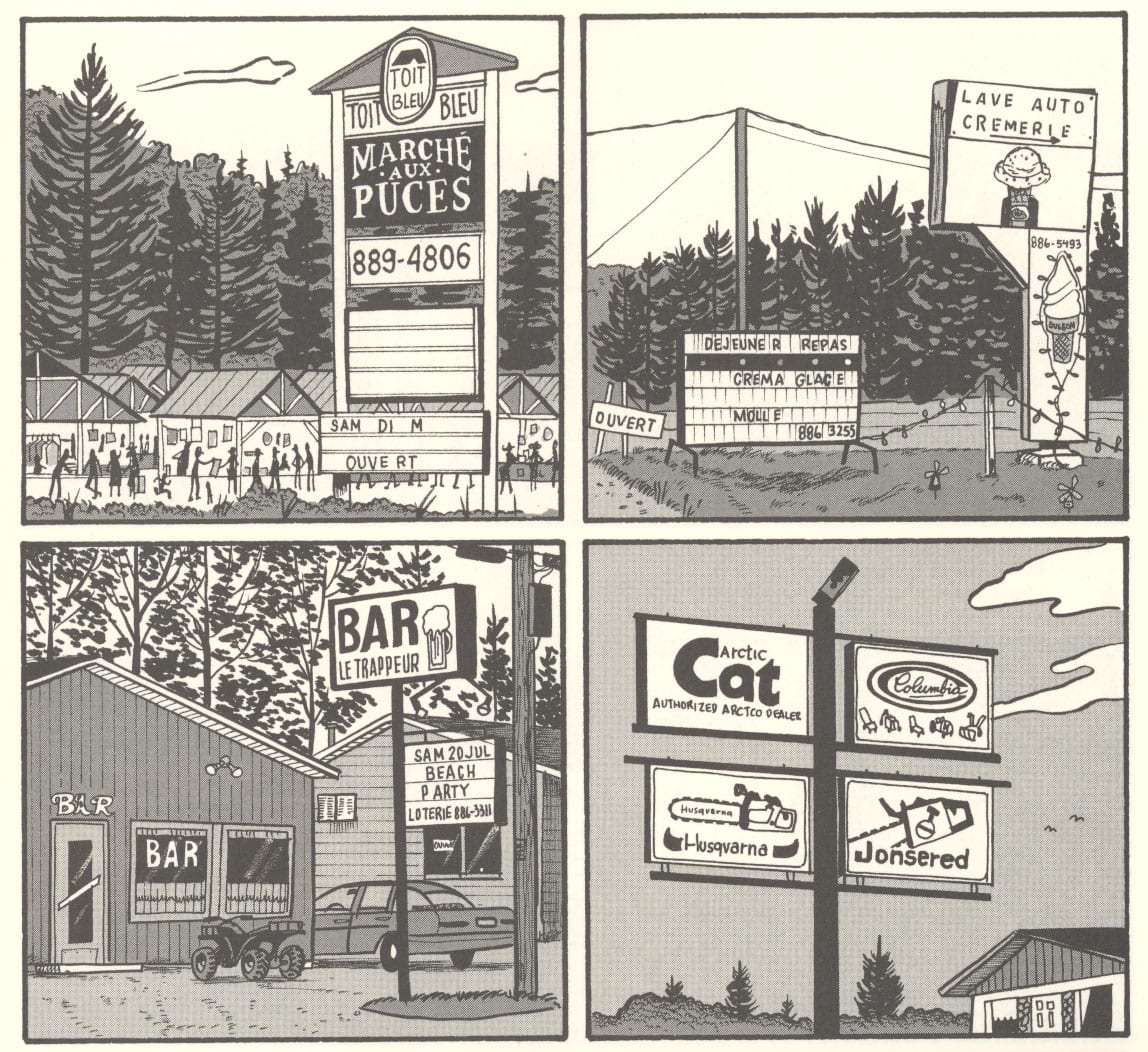

Another such motif highlights Paul’s somewhat abstracted relationship to nature. At the beginning of Fishing, even before the dinner party with France and Peter, Paul is at a photo shoot, collaborating with a photographer and a model on an advertisement for office furniture. After Paul designs the ad and sends it to the printers, he and Lucie go on vacation, time off they’ll spend with members of Lucie’s family at a rustic lake campsite. While heading out of town, Paul spots his furniture ad on a billboard, and his passion for graphic design continues during the long car ride to the lake. Numerous panels showcase the signage Paul and Lucie see as they travel from the city to the woods:

Amusingly, both Paul and Rabagliati pay more attention to signs for bars and hardware stores than to the nature around them. In one memorable panel, Paul and Lucie’s car bounces up and down tree-dotted hills as Paul says, “I guess we won’t find a Burger King on this road!” No, he won’t. He’s out of his element, and some of Fishing’s humor comes from Paul’s shocked reactions to fishermen decapitating fish and teenagers in the camp who torture rabbits.

The symbol for Paul’s growing intimacy with nature is an apple growing on a tree. While at the campsite, Paul goes for a long walk with Lucie’s sister Monique, and Paul rants about how contemporary hunting and fishing are “rigged”: the fisherman uses full-proof lures and equipment to catch his fish, and the Canadian government stocks lakes with perch and bass to make fishing easier. Monique responds by arguing that even a compromised version of hunting speaks to man’s “natural instinct,” but that Paul’s too much of a city boy to understand this. Then she asks a question:

Later, at the picnic with France and Peter, Lucie wanders off by herself. Paul joins her. In several panels, we see them standing under an apple tree, their bodies in silhouette. Paul reaches up, plucks an apple off a branch, offers it to Lucie, and then takes a bite himself. Paul began Fishing somewhat blind to the beauty and cruelty of nature, but he understands blood and bone better after Lucie’s miscarriage.

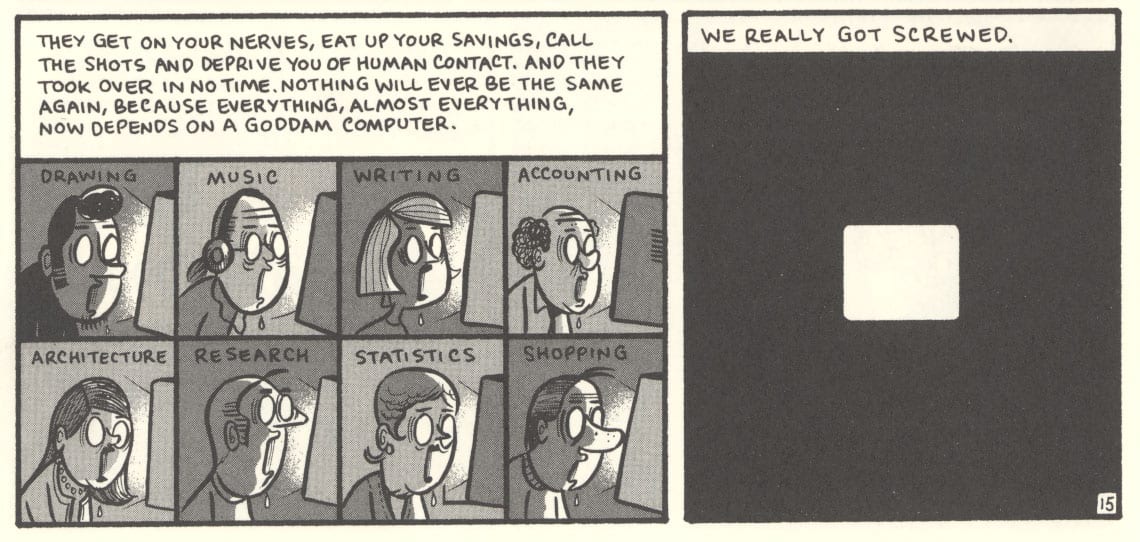

In addition to these reoccurring motifs, the overall structure of Fishing alternates between a present-day chronicle of Paul and Lucie’s vacation (and their miscarriages and the eventual birth of their daughter) and flashbacks that address a single theme: the pain that humans feel when trapped in an inhuman situation. Bad jobs in particular are Rabagliati’s central target. Early in Fishing, Rabagliati segues from Paul designing the furniture ad on his computer to a screed against the adoption of computer technology in the graphic design and printing fields. “Overnight, dozens of typographers, color separators, and film strippers closed shop” (13), Rabagliati writes, and one of them is his father, rudely discovering that his “Typographer” skills are now out of date. Traditional industrial printing is replaced by lonely designers spending outlandish amounts of their personal money for computer upgrades. The sequence ends with Rabagliati extending his critique to every aspect of 21st century computer culture:

Obsolescence and the negative effects of change dominate other flashbacks in Fishing too. While wandering around the cabin, Paul imagines the raucous lives of all the hunters who’ve slept in the cabin since the 1930s, and prior to the “rigged” culture of hunting and fishing today. Clément, an avid fisherman and Monique’s husband, gets an extended flashback about his job history in the aviation industry. When he began his job in 1971, Clément “felt good about being part of a big team effort” (72), but his bosses have since ruined his working conditions by listening too much to productivity experts, and by maximizing profits through massive, demoralizing layoffs. As Rabagliati describes Clément’s job situation—“Too old to try something new, too well paid to leave … he feels trapped”—a panel shows a fish biting Clément’s hook (77). Both man and fish are screwed.

Paul empathizes with his father and Clément for reasons beyond his love for both men; Paul too has been the victim of intolerable circumstances beyond his control. After Lucie tells Paul that she was an honor student, Paul flashes back to his own educational failures—“I never had an average of more than 40% or 50% on my report cards” (88)—and details the humiliation he felt in remedial classes and summer school. My favorite panel in Fishing, one that always makes me laugh, shows Paul sitting in a “special” math class, listening to a condescending teacher trying to impart basic life skills to a “bunch of hopeless morons” (88):

Paul hates his secondary education. He is bullied in public high school, and when he transfers to a private school, several factors (teachers with thick foreign accents, a draconian dress code, and impenetrable student cliques) make him so miserable that he decides to run away from home. He plans to leave Montreal on his bike, until an encounter with a poor street kid and a dying dog convinces Paul to return home to his loving parents. Paul hates school like Clément hates his job: both are victims of institutions where one-size-fits-all social engineering trumps human values.

Some of the flashbacks in Fishing, however, are more optimistic about the possibility of individual happiness. During a rainy day, Paul, Lucie, Monique, and Monique’s children Judith and Mylène drive to a nearby museum dedicated to Louis Cyr, a weightlifter “once considered the strongest man in the world” (116). Rabagliati then drops a two-page biography of Cyr into his narrative—and Cyr lived a big, fanciful life, overjoyed to travel the world and participate in strongman competitions. Later, during her walk with Paul, Monique talks about her job as a counselor to at-risk mothers and children in Montreal’s poorest neighborhoods, and from the stories she tells (she comes close to violating professional ethics by adopting the son of one of her clients) it’s clear she passionately cares about the families she serves. If the flashbacks involving Paul and Clément illustrate a mournful disconnect between people and their situations, then the flashbacks with Monique and Louis Cyr exhibit more hope for fulfilling jobs and meaningful lives.

Lucie is on her own search for meaning too. In the last third of Paul Moves Out, the book that chronologically precedes Fishing, Lucie and Paul babysit Judith and Mylène, and Lucie discovers that she desperately, achingly wants to be a mother. And yet she miscarries. Although Lucie’s problem is biological rather than institutional, she knows (like Paul and Clément do) how it feels to be trapped in a situation that blocks you from being the person you want to be.

Much of Fishing’s complexity is a result of narrative organization—bookends, echoes, repeating themes—but Lucie’s desire to be a mother (ignited in Moves Out, delayed but finally realized in Fishing) shows how Rabagliati’s discrete books gain resonance as part of the overall Paul series. Readers familiar with other Paul graphic novels (especially Moves Out) are glad to see members of Lucie’s family reappear in Fishing, and Paul’s family is important too. When Paul returns home from his failed attempt to ride away from Montreal, his parents never mention the note he left claiming that he’ll be gone “forever,” allowing Paul to save face and deal with his unhappiness on his own when he returns. Every Rabagliati story since “Paul, Apprentice Typographer” depicts Paul’s father as a kind, sensitive person (though oddly enough, Rabagliati writes much less about his mother), and in Fishing Dad even has a heroic scene where he saves Paul and himself from sinking in a leaking boat.

A different example: in the first half of Paul Moves Out, Paul and Lucie are students at the same Montreal art college, and declare their mutual love after returning from a field trip to New York City. Immediately after getting off the train, Paul invites Lucie to his house for dinner with his parents. Then Paul drives Lucie to her parents’ house, where he meets Lucie’s father for the first time:

Logically, we’re limited to Paul’s shallow impression of Lucie’s father—he “seemed nice enough”—but we aren’t even told his name (Roland). He’s not yet a significant figure in Paul’s life, but he will be: The Song of Roland is a 100+ page tribute to his father-in-law’s life, particularly his graceful final days in a palliative care clinic. The presence of family members across multiple books is just the most obvious example of how Rabagliati’s work balances the demands of the self-contained graphic novel with serial fiction. Paul’s story spills over multiple graphic novels, creating a loose but consistent chronology for Paul/Rabagliati’s life, and rewarding readers who read all of Paul.

Of course, this promotion of a bit player to a central role isn’t unique to Rabagliati. Because I read her books relatively recently (as an adult, out loud to my kids), the first writer I think of is Beverly Cleary, who began her career writing about paperboy Henry Huggins, then introduced sisters Beezus and Ramona Quimby as second bananas in the Henry stories, and finally made Ramona the center of an even more memorable series of books. (TCJ readers can surely come up with more highbrow examples.) Rabagliati’s elaboration of Roland’s life also reminds me of Marc Singer’s commentary on Grant Morrison’s Invisibles, particularly a story titled “Best Man Fall” (Volume 1, #12, September 1995) where a redshirt extra becomes, for the duration of a single comic book, a star.

Singer’s analysis of “Best Man Fall” appears in the anthology Critical Approaches to Comics: Theories and Methods (Routledge, 2011), edited by Matthew J. Smith and Randy Duncan. The purpose of Critical Approaches is to introduce students to concepts they can use to analyze comics—for example, Joseph Witek writes about different modes of caricature, Andrei Molotiu writes about abstract form, and Leonard Rifas writes about ideology (in Tintin in the Congo!). Singer’s topic is “Time and Narrative,” and he begins with general comments about the elastic relationship between storytelling (including comics storytelling) and time: “Even the most apparently chronological narratives often depart from strict chronological time. They may begin in the middle of the action, recall earlier events, skip over large periods of time, compress or extend their descriptions of key moments, or present the same incidents multiple times” (56).

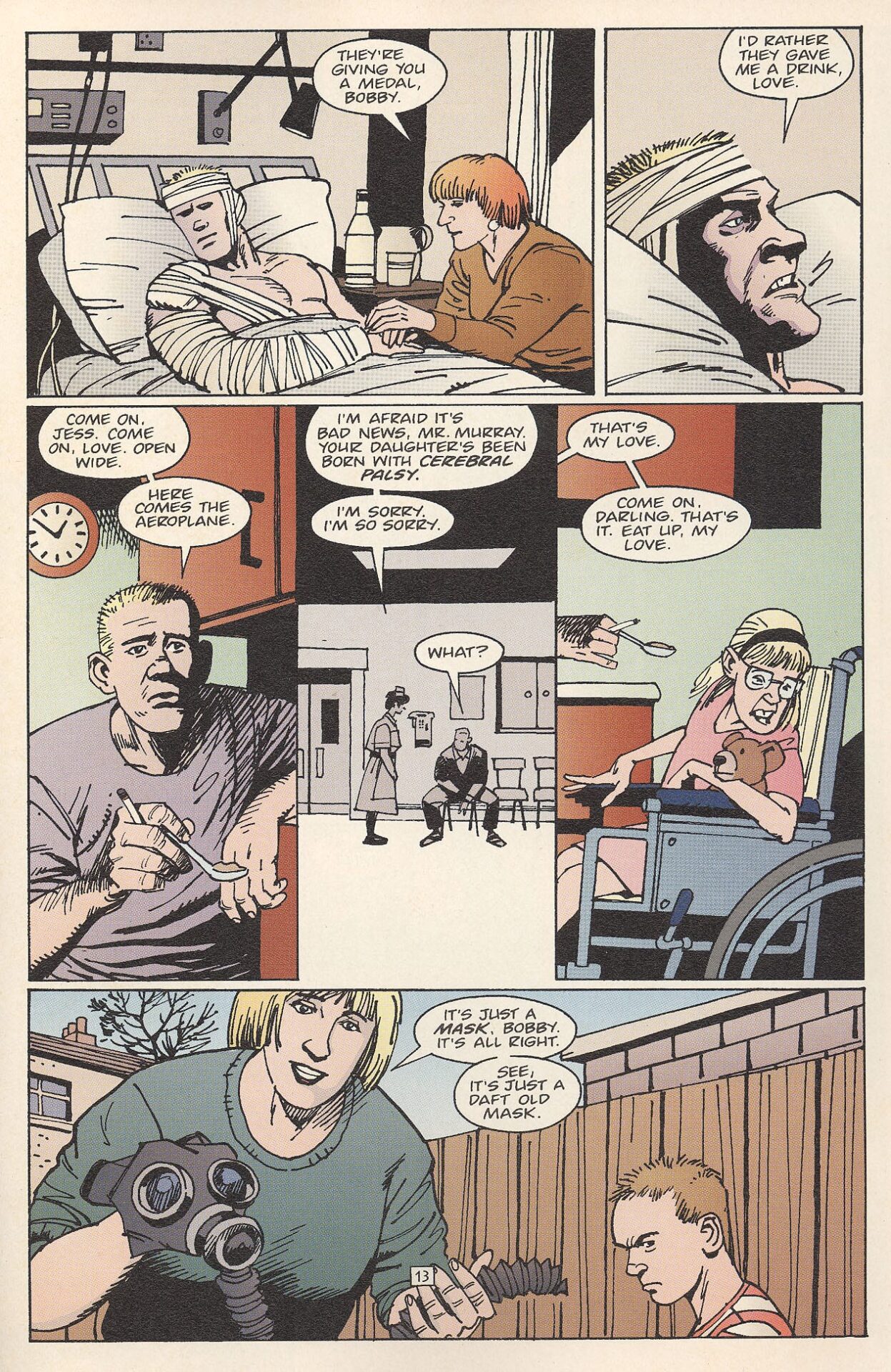

All these techniques (and more) are present in “Best Man Fall,” which chronicles the life of Bobby Murray, a British ex-soldier who takes a job as a security guard in a prison. In Song of Roland, Rabagliati elevates his father-in-law to center stage; Morrison and artist Steve Parkhouse do the same with Murray, who we first see as a faceless flunky shot by “ontological terrorist” King Mob in the very first issue of The Invisibles (September 1994). As Singer writes:

The security guards were just so much cannon fodder, unthinking henchmen of the forces of evil and minor obstacles for King Mob to dispatch with righteous violence. After “Best Man Fall” presents the combat from Bobby’s point of view and recontextualizes it within the rest of his life story, however, the battle is no longer an entertaining diversion but a tragedy, and King Mob’s actions are not heroism, but murder. (64)

Singer points out that the flashbacks that do the contextualizing in “Best Man Fall” defy clarity of storytelling, and opt instead for “a series of abrupt transitions and disordered vignettes that jump from moment to moment in the life of Bobby Murray, with no regard for chronology” (61). Morrison challenges readers to make sense of the gaps between seemingly unrelated panels, to follow the connections among scenes split across multiple pages, and to figure out the contours of Murray’s life from the fragments and recursions of “Best Man Fall.” Here’s a sample page:

Many of the transitions between panels on this page—particularly between panels five and six, which hops from an adult Murray feeding his daughter to a scene decades earlier, when he was a toddler—are abrupt, and Morrison refuses to insert captions like “Five years later” to ground the reader in a definitive chronology of Murray’s life. Rather, Morrison leaves us to figure out the puzzle (or not). Yet because one panel follows another on the page, we still search for links between them. Did Morrison place panels five and six in a sequence because he wanted the adult Murray to remember his mother’s words (“It’s just a mask, Bobby”)? Given his interest in metaphorical metaphysics, is Morrison arguing that the disabled body of Murray’s daughter is just a “mask”? Are our bodies false illusions that we will eventually transcend?

Morrison’s radicalism here is very different from the accessibility that characterizes the Paul series, but Morrison and Rabagliati both work in serial installments, design their “chapters” to be parts of a larger vision, and take an insignificant character from an earlier chapter and flesh him out into a three-dimensional personality. Singer argues that The Invisibles demonstrates “how comic books can creatively represent, rearrange, and exploit time on the level of the panel, the page, the issue and the series” (69), and I’d stake the same claim for Rabagliati’s Paul.

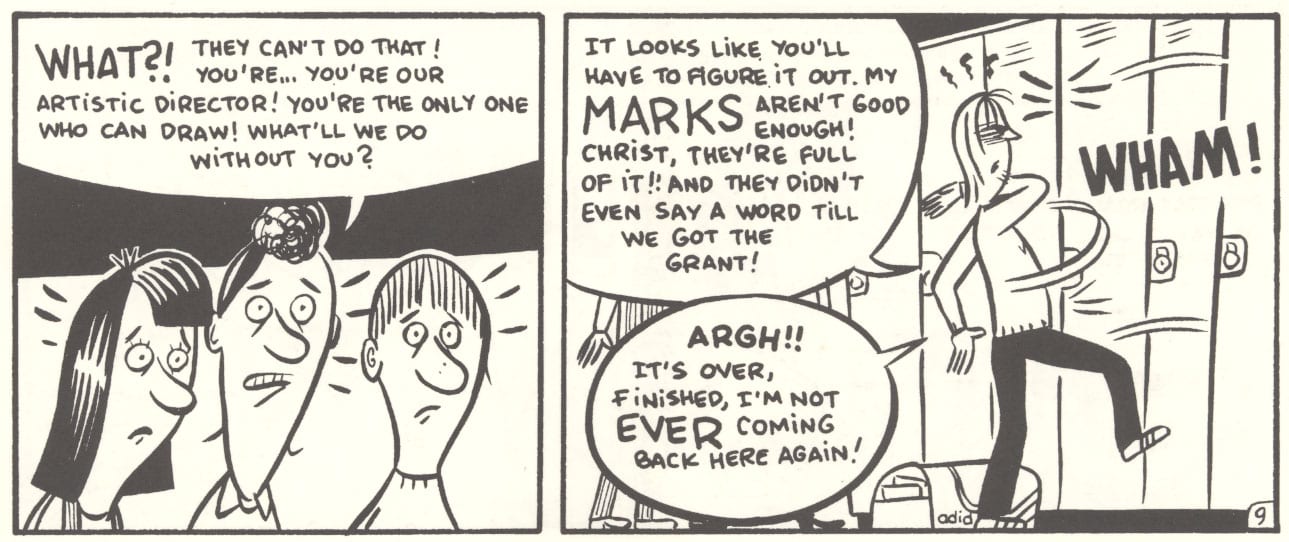

Rabagliati’s freedom to choose different characters to highlight in various scenes and books is complimented by the rough chronology of Paul's life that percolates underneath the entire series. The most important period in Paul’s life, for instance, only becomes clear to readers who assemble the chronology from various clues and hints. We’ve already discussed Paul’s halfhearted attempt to ride away from home as a teenager, and further elaboration on his miserable high school days opens Paul Has a Summer Job, where we find out that Paul quit high school in eleventh grade because the principal refused to allow him to work on a big art project:

In the summer of ’79, after he leaves school, Paul labors at a grindingly boring job printing lottery tickets, and stagnates until a friend calls to offer him a position as a counselor at a summer camp. The rest of Summer Job shows Paul regaining his joie de vivre at the campsite, as he becomes good friends with the other counselors (especially Annie, to whom he loses his virginity) and discovers his talent for working with kids. Then the story continues in Paul Moves Out: Paul has returned from the camp and enrolled in a commercial art school.

Paul’s first year in art school is mixed. Rabagliati writes that the teachers and assignments “hadn’t changed in decades” (10), and ill-prepared students for a career in graphic design or illustration (especially with the paradigm shift of personal computing right around the corner). Paul does, however, makes friends with the other students (particularly Lucie), and falls into a comfortable routine living at home with his parents. And then Rabagliati jumps forward in time and surprises those of us keeping track of the events of Paul’s life:

“I worked at a summer camp up north”: Paul was a counselor at the camp for two summers, not just the summer of ’79, a fact never mentioned in Paul Has a Summer Job. Maybe Rabagliati will return to the summer camp and the summer of 1980 in a future graphic novel.

Immediately following their reunion, Paul and Lucie discover that one of their teachers will be Jean-Louis Desrosiers, who stresses graphic design in his classes and who is an intellectual mentor to Lucie, Paul, and their friends. Desrosiers lectures about Milton Glaser and Paul Rand; he also encourages Paul and Lucie to study such culturally significant figures as Mise van der Rohe and Orson Welles, and drags them to a screening of Marguerite Duras’s India Song (1975). He also organizes the “cultural trip” to New York City where Paul and Lucie fall in love. During the two-year period from summer 1979 through spring 1981, Paul’s (and Rabagliati’s) life is irrevocably changed: he sheds his post-school angst, he has sex, he enrolls in art school, he is introduced to the subject of his first career (graphic design), he opens himself up to modernist art and culture, and he meets and falls in love with Lucie. The miraculousness of this period, however, is only evident to readers of both Paul Has a Summer Job and Paul Moves Out.

I can’t believe that I ever found Rabagliati’s art “simple,” especially now, because I’m having trouble ending this essay, having trouble shutting up about all the themes, connections, and tangents in his comics. (Why, for instance, do so many of Paul’s epiphanies occur when he’s traveling, i.e. to the summer camp, to New York, to the cabin on vacation? Is this related to his portrayal of death as a journey, as in the sequence that ends Song of Roland where Roland’s spirit ascends into the sky?) It’s time for me to shut up, though—until I see what Paul Joins the Scouts adds to this remarkable life.