Early the afternoon of May 16, a message appeared on the various official websites and social-media outlets of the Brooklyn Comics and Graphics Festival:

Thank You and Good Night

We have decided not to continue with BCGF. We had a great run and thank all of our colleagues for their support.

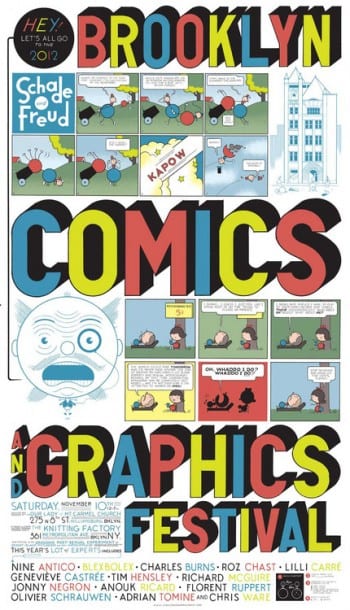

While rumors of troubles between the festival's three founding partners had been spreading over the past few months, the announcement still took many by surprise. Since its 2009 founding by three prominent members of the independent comics world—Gabriel Fowler, owner of Desert Island; scholar and programming coordinator Bill Kartalopoulos; and Dan Nadel, publisher of PictureBox (and co-editor of this website)—the Brooklyn Comics and Graphics Festival, held every winter at the Our Lady of Mount Carmel church in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, had become one of the most influential, admired, and seemingly successful festivals for independent comics in the United States, and was seen as a model for several similar-minded shows that arrived in its wake. The abrupt announcement of its demise led to widespread dismay and surprise.

One of those expressing surprise at the announcement was founding partner Gabriel Fowler himself. When asked late yesterday to confirm the accuracy of the announcement, Fowler replied via e-mail, "You'll have to ask the person who posted it," and added that the message was not posted with his blessing. Fowler says that he wished to continue the show, but was prevented from doing so by his partners. He blames "interpersonal fallout" for the show's demise, and explained: "Dan wanted to step away from the show due to other commitments, and I then failed to come to terms with Bill. I wanted to continue the show on my own and was told that it was impossible."

One of those expressing surprise at the announcement was founding partner Gabriel Fowler himself. When asked late yesterday to confirm the accuracy of the announcement, Fowler replied via e-mail, "You'll have to ask the person who posted it," and added that the message was not posted with his blessing. Fowler says that he wished to continue the show, but was prevented from doing so by his partners. He blames "interpersonal fallout" for the show's demise, and explained: "Dan wanted to step away from the show due to other commitments, and I then failed to come to terms with Bill. I wanted to continue the show on my own and was told that it was impossible."

Fowler says that he ultimately proposed "transforming the festival into a non-profit organization with a larger board of directors to diffuse any interpersonal tension," but says that this proposal was rejected. What exactly were the terms that Fowler and Kartalopoulos failed to agree upon? "I'd rather not get into this, but it hinges on ownership of the festival," Fowler says. "I was also hopeful that the formation of a non-profit organization would diffuse ego-driven issues related to ownership."

Dan Nadel acknowledges via e-mail that he and Kartalopoulos made the announcement without Fowler's involvement. "Bill and I felt it was necessary, and the majority has always carried the vote with BCGF." However, he disputes some of Fowler's claims about the reasons for the show's ending. "I don't think it was personal so much as business," Nadel wrote in an e-mail. "Due to various professional obligations and time constraints, I no longer wanted to be involved, but stayed on to (I hoped) ease the transition into it being either a two-person organization or to help bring in a third to replace me. This transition proved more difficult than any of us anticipated. Without getting into too many details, we could not agree on terms for how the show should proceed. We offered Gabe a number of ways to continue the show, but he refused all terms, and ultimately negotiations broke down. That was effectively the end. Without any way to resolve the issues at hand, we were forced to call it a day. I want to make clear that I really hope there's no ill will around this. I have a huge amount of respect and affection for Gabe and Bill both. This bit of business just couldn't be worked out."

Reached by telephone, Bill Kartalopoulos says that the announcement "reflected a majority agreement of the partnership that organizes the Brooklyn Comics and Graphics Festival."

Asked to give his version of the events leading to the festival's dissolution, Kartalopoulos says that "the Brooklyn Comics and Graphics Festival has always been a collaboration between PictureBox (i.e., Dan), Desert Island in the person of Gabe Fowler, and myself. The festival has been a product of that collaboration. We collaborated for four years, we put together four great festivals. Even though I expect to continue to work with both of those guys in a variety of ways, we’re not collaborating anymore, so the show, which I think is very specifically a product of the collaboration of the three of us, has probably come to a natural end in part for that reason."

Kartalopoulos elaborates: "The other thing I would say is that the Brooklyn Comics and Graphics Festival has been a very successful event. Every year it grew beyond our expectations. I think anyone who was at the 2012 show probably observed that the festival was sort of maxing out the structure that had been built to support it. I mean both literally in terms of the space and also, I would say, organizationally. Growth is hard, and presents a lot of challenges. I think that the 2012 event represented the peak of what could be accomplished within the constraints of the current model. So even though I’m sad and upset in certain ways, I am happy to go out on a high note rather than start hitting walls."

Kartalopoulos also dissents from Fowler's characterization of the partnership dispute as hinging on ownership and interpersonal issues. "Among the majority of the members of the group I don’t think there were too many questions about the ownership of the show," he says. "My point of view is that the festival existed as a collaboration between three people, and to the extent that for four years we were able to stay on the same page, it worked. I don’t know that I would say that there were interpersonal issues because I liked everyone who was involved with the festival. I think there were just differences on how to deal with the challenges of growth."

Kartalopoulos says that once the partners were no longer able to agree on the same direction, the show was basically unable to continue. "I think that based on the results of last year’s festival, to continue we would need to rethink the event," Kartalopoulos says. "We had a lot of shared momentum up to that point, and I think once three people start rethinking an event, there is a lot of possibility for them to start thinking about it in different ways that they don’t necessarily share."

Asked to comment on Fowler's proposal to turn the festival into a nonprofit, Kartalopoulos demurs. "There were a lot of ideas that were tossed around at various points over the years, and I don’t really want to get involved in any kind of re-litigation of any conversation about that kind of stuff," he says. "I don’t think it is helpful or productive. I mean, you could probably come up with twelve different visions of the future we came up with at different points and I wouldn’t want to single out any one in particular. I think probably the more important barter point is just that we collaborated with a similar mindset for four years, and I think we responded to the challenges of the growth of the festival with different ideas. As a result of which we’re just not collaborating anymore."

When informed of Kartalopoulos and Nadel's responses, Fowler disagrees strongly. "While it's true that the BCGF evolved into a three-person collaboration, it didn't start that way," Fowler writes. "It started with me alone, looking for venues and approaching artists and publishers. I started the show and would prefer to continue it, but I guess I don't have the right if these guys don't agree. What else can I say? I'm not a lawyer, but I resent being put in this position. All of the other details are meaningless to me."

One thing all three founding partners do agree upon is that despite some of the speculation on social media from outsiders, the show's demise had nothing to do with financial issues. "The festival has been a ton of work for very little financial reward, but it was essentially self-sustaining," says Fowler.

"It was both profitable and artistically rewarding," says Nadel. "It wasn't making a fortune, but by publishing standards it wasn't bad at all."

"As far as I’m concerned, money-making has never been a consideration," says Kartalopoulos. "The festival just needs to support itself." But he does think that the perception brings up issues worth discussing. "There’s a bigger infrastructural point here which is that a big part of the indie comics economy at this point seems to rest on the shoulders of people who work very hard for very little reward to create these festivals," he says. "I think there are some structural issues that I hope people will start talking about, even if not as a direct result of this situation. It’s really hard and it’s really a lot of work to put together these festivals. No one is making money personally doing these things, and you can’t have an industry that depends on volunteer labor forever.

"These festivals have become so important, because there’s also a real distribution problem that the festivals are being asked to compensate for," Kartalopoulos adds. "These are tangential issues, but they just come up in my mind when people talk about Is the festival financially sound? I'm like, Well, no! Duh! This whole industry is not financially sound. If it weren’t for people working against their financial interests we wouldn’t have an indie comics world.

"Putting that aside," he continues, "the show always broke even, plus a little bit. I spent some time looking into larger venues, and I think that some of those could have worked out financially if there was the organizational will to make them work. With a bigger space certainly the costs do skyrocket in New York, but there was an opportunity to potentially include more exhibitors and increase those revenues. Even though it was always a part of our ethos to keep the table costs as low as possible, I think the festival was financially successful enough for most exhibitors that there could have been some logic to increasing the table cost a little bit to compensate for the increased cost of a larger venue. I don’t think it was any more unsustainable than any other festival."

Nadel wishes things could have ended differently for BCGF. "Ideally Bill and Gabe would've figured out a way to move forward, but that's not happening," he says. "I sincerely hope something else pops up, or one of those guys starts their own festival."

"I think we all feel a little sadness that the festival is ending," Kartalopoulos agrees. "It’s the ending of a collaboration."

But Kartalopoulos thinks it is important to point out the successes of the festival, as well. "A lot of things that have a big cultural impact don’t necessarily stick around too long," he says. "The history of art and culture is full of things that lasted a few years, reached the end of their normal lifespan, but continue to have an influence. I mean, not to put it on the same level, but there's a punk show at the Met, you know? Most of those bands didn’t last more than a couple of years. There’s no question that over the past four years the Brooklyn Comics and Graphics Festival has inspired a lot of other festivals around the country. You could probably come up with a list of at least half a dozen festivals that have come up since then that have at least a little piece of the Brooklyn comics festival DNA in them, from having a really art-comics-focused festival, to a curated show as a model, to free-to-the-public as a model, to having a lot of off-site events that aren’t just all in some depressing convention hall, to using and integrating with the city. I mean, you could look at CAKE or The Projects. I’m looking forward to Autoptic in Minneapolis this summer, which I think should be really interesting. I think there’s a lot of this kind of stuff popping up now, and I think the show has had a really huge influence. If you are able to articulate a new vision specifically and clearly and powerfully enough you don’t necessarily have to say it over and over again, and I think in terms of articulating a different kind of vision for an independent comics festival in America, the Brooklyn Comics and Graphics Festival could not have articulated that more clearly or loudly than we did over the past four years."

Kartalopoulos ended on a further positive note. "I’m very proud of everyone who was involved with the show and what we accomplished, and I am just really grateful to anyone who ever exhibited at the show, came as a guest, or came to check it out, and am grateful to Gabe and Dan for all of the hard work they did to make it happen."

This article has been slightly edited for content and grammar since its initial publication.