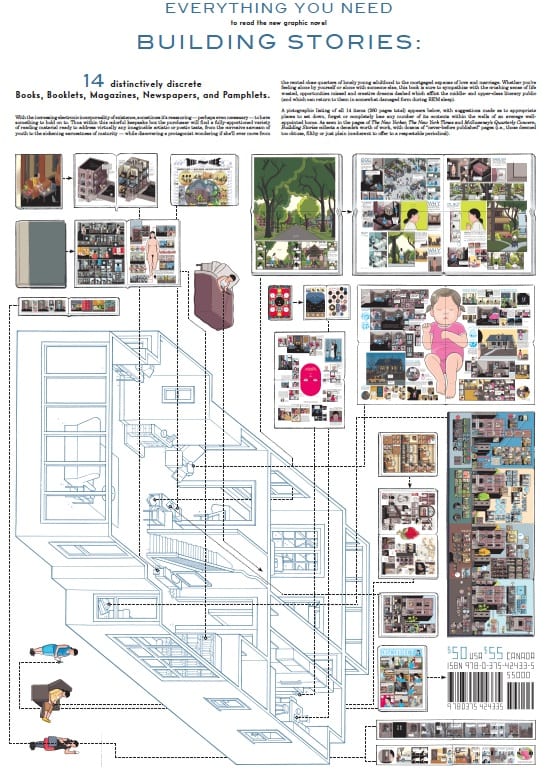

To mark the release of Chris Ware’s decade-in-the-making Building Stories—a box of fourteen print artifacts ranging from cloth-bound volumes and newspapers to broadsheets and silent flip books—The Comics Journal is featuring a series of essays from the contributors to the 2010 volume The Comics of Chris Ware: Drawing is a Way of Thinking (University Press of Mississippi). Each contributor is revisiting the argument they made in that edited collection two years ago in light of the newly released work, speaking to the ways in which Ware’s comics have either transformed in that time or are returning to the themes of his earlier publications. We hope these first thoughts give rise to a spirited discussion about a novel that will shape conversation in the medium in the years to come.

In my contribution to the anthology The Comics of Chris Ware: Drawing is a Way of Thinking, I talk about Chris Ware’s delicate relationship with museums and the fine art establishment, exploring how Ware stakes out a position as an artworld outsider, despite being lauded by these same institutions. In the intervening years since the book’s publication, Ware’s work has continued to find a welcome home in museums and gallery spaces. As I unboxed Building Stories, sitting on the floor and slowly spreading out its wondrous contents, my first thought was of Marcel Duchamp’s Box in a Valise, his “portable museum” that allowed him to carry miniature replicas of his work in a travel case. Indeed, Ware recently cited Duchamp’s work as an inspiration, mentioning it in the same breath as a French game box from the 1920s (this effortless knack for combining high and low source material being an unfaltering feature of his work.) It strikes me that the immediacy and tactility of Ware’s project, while undoubtedly intended as a counterpoint to the Kindle-ization of our reading habits, also functions as a way of bringing his work off the white walls of the gallery and out of the museum vitrines in order to create an intimate connection with his readers. Interactivity has become a deadening cliché of exhibition design, as museums race to embrace smart phone audio tours and social media outreach in their attempts to get visitors to engage with art. Ware’s work demands the viewer’s active participation without resorting to technological tricks.

The objecthood of the work asserts itself from the moment you open the box; it is messy and present. It demands that the reader pick up and examine each element and decide how they want to navigate the material (the bottom of the box does include a diagram with directional cues, but I did not come across it until after reading all the material in a self-selected, haphazard order.) It becomes a physical experience: unfurling the newspapers, flipping through chapbooks, handling the game board, each of which is carefully crafted and exquisite. The pieces are architectural fragments, building upon each other and accumulating meaning. Poring over the box’s contents makes you reflect on the unpredictable nature of memory, as certain events take on more significance as the back story reveals itself. It is as if you have been given your very own Joseph Cornell box to puzzle over and marvel at.

The objecthood of the work asserts itself from the moment you open the box; it is messy and present. It demands that the reader pick up and examine each element and decide how they want to navigate the material (the bottom of the box does include a diagram with directional cues, but I did not come across it until after reading all the material in a self-selected, haphazard order.) It becomes a physical experience: unfurling the newspapers, flipping through chapbooks, handling the game board, each of which is carefully crafted and exquisite. The pieces are architectural fragments, building upon each other and accumulating meaning. Poring over the box’s contents makes you reflect on the unpredictable nature of memory, as certain events take on more significance as the back story reveals itself. It is as if you have been given your very own Joseph Cornell box to puzzle over and marvel at.

I previously wrote about Ware’s facility with art historical conventions, which are once again on display here. The Renaissance system of linear perspective, use of symmetry, repetition of geometric forms and motifs, along with a resounding clarity of both color and line brings unity to the disparate pieces. This visual precision and orderliness sharply contrasts with the inherent messiness of his characters’ emotional lives. His main character is a woman who perceives herself as a failed artist; her tender drawings forming a counterpoint to the stark linearity of Ware’s compositions. In the smaller of the two included bound books, his cutaway views of her apartment building recall the tradition in seventeenth century Dutch genre scenes that depicted domestic interiors from the perspective of an unseen observer.

At the same time, the cutaway technique is also reminiscent of the children’s books of Richard Scarry, with their carefully labeled cutaway drawings. While Scarry labeled his pictures with text cheerily indicating what people do all day, Ware’s building has its own narrative voice, rendered in careful cursive lettering, its labels bearing equal witness to life’s tragedies (29 broken hearts) and its banality (231 drain clogs). The connection to picture books is further cemented by the dimensions of the small book, and its gold leaf spine, which are immediately recognizable as the hallmarks of the Little Golden Book series. Indeed the book’s endpapers, with their allover pattern of leafy vines, flowers, and animals (flowers being a recurring theme in the work, and the animals—a cat, mouse, bee, raccoon, and fly, all connect back to the overarching story) continues the homage to Golden Books. Ware’s decision to reference a children’s book design reverberates with the theme of parent-child relationships that permeates the work. Beyond that, comics have long been derided in some circles because of a perceived connection to childhood. Here Ware celebrates the connection, and showcases the comic medium itself by including representative examples of all its sundry forms: comic books, mini-comics, newspaper comics, chapbooks and picture books. Just as Duchamp included diminutive models of his greatest works in his traveling suitcase museum; Ware has created a miniature pantheon of comic art, taking it out of the museum and off the computer screen and giving us all something we can hold on to.

At the same time, the cutaway technique is also reminiscent of the children’s books of Richard Scarry, with their carefully labeled cutaway drawings. While Scarry labeled his pictures with text cheerily indicating what people do all day, Ware’s building has its own narrative voice, rendered in careful cursive lettering, its labels bearing equal witness to life’s tragedies (29 broken hearts) and its banality (231 drain clogs). The connection to picture books is further cemented by the dimensions of the small book, and its gold leaf spine, which are immediately recognizable as the hallmarks of the Little Golden Book series. Indeed the book’s endpapers, with their allover pattern of leafy vines, flowers, and animals (flowers being a recurring theme in the work, and the animals—a cat, mouse, bee, raccoon, and fly, all connect back to the overarching story) continues the homage to Golden Books. Ware’s decision to reference a children’s book design reverberates with the theme of parent-child relationships that permeates the work. Beyond that, comics have long been derided in some circles because of a perceived connection to childhood. Here Ware celebrates the connection, and showcases the comic medium itself by including representative examples of all its sundry forms: comic books, mini-comics, newspaper comics, chapbooks and picture books. Just as Duchamp included diminutive models of his greatest works in his traveling suitcase museum; Ware has created a miniature pantheon of comic art, taking it out of the museum and off the computer screen and giving us all something we can hold on to.