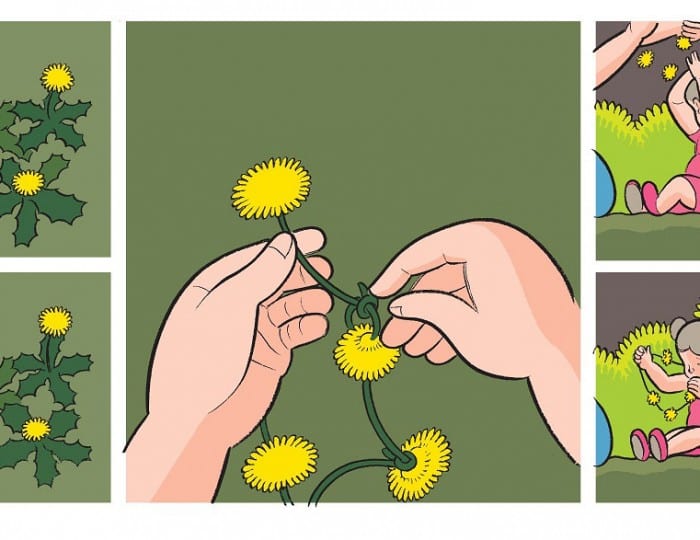

Whatever your feelings regarding Chris Ware, you can't fault him for ambition. Just looking at the sheer size of his latest project, Building Stories, is enough to spontaneously induce low whistles of awe. Building Stories is not actually a book per se but an oversize box, roughly the size of your average Milton Bradley board game, containing 14 comics of different shapes and sizes, from a pocket-sized mini-comic to a volume designed to resemble a Little Golden Book to a pamphlet designed to fold out like a newspaper.

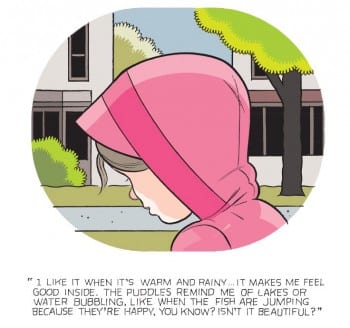

Designed to be read in any order, the collection focuses on an unnamed, one-legged woman and follows her life experiences both as a lonely twenty-something living in a Chicago apartment house and, years later, as a married suburban mom and housewife. In between we get glimpses of other people’s lives, including those of the elderly landlady of the aforementioned apartment house, the bickering couple that lives downstairs, and an anxiety-prone bee.

Ware is currently in the midst of a whirlwind tour across the United States to promote Building Stories, but he graciously took time to answer a few questions over email about the work and its creation. It was a genuine pleasure to have the opportunity to throw my overly verbose questions at him and I hope his answers help illuminate what I regard as one of the most thoughtful, moving and utterly unique comics of the year.

CHRIS MAUTNER: While there have been themed boxes of comics before -- I'm thinking of Non #5 and the Actus Tragicus box -- I don't think any individual cartoonist has attempted something on the scale of Building Stories. How did the idea of putting together a "box of comics" come about? And did the concept come to you before you started the work or did it take shape organically, as you developed the story?

CHRIS WARE: I guess it happened simultaneously with the story's development, though I'd wanted to do a box of comics since 1987, when I proposed it as a second project to Eclipse comics (and which they justifiably declined). I made two or three small or single editions of boxed little comic books in art school, though held off on the idea until 2006 when I suggested it to Pantheon. I was surprised they agreed, and that it all actually worked out. Originally I'd thought the books would divide and encompass the characters living in the apartment building, but as the story changed and it became clear that the entire story was filtered through the mind of the woman on the third floor, the structure of the book changed to reflect that, and now I think (I hope) it's much more interesting as a result. Finally, while I don't want to give too much away, I think at one point or another everyone has a dream where they read a surprising book, or see a huge, complicated painting, or hear a moving song and then wake up and realize that they'd created the whole thing, alone, in their mind.

MAUTNER: Perhaps it's an obvious point, but it struck me that you're giving up a certain amount of control by allowing the reader to shape the order in which its read. Did you find yourself having to rethink the way you structured your comics or the way you build a narrative when making Building Stories? If not, were there any unexpected challenges that came up in its production?

WARE: Absolutely. This was, of course, very intentional. I wanted to get more at the way stories and memories are available from all sides and moments in our memories, and not really part of a continuum; I don't think we have a "book of life" in our brains through which we thumb to find chapters and passages; our memory is more like a gem or a flower or a three-dimensional something that we can turn and turn inside out and get into and out of. As well, given that it's a comic book, it grows from panel to page to pamphlet to, finally, a package or a present.

Of course, I also hoped ultimately that the book would just be fun, for lack of a better word.

MAUTNER: The Branford Bee stories are done in a very simplified, almost abstract style where you're breaking down the characters to their essential cartoon elements of basic lines and circles. It's a style you've used elsewhere; the McSweeney's anthology comes to mind. I was wondering how you developed that particular style and why you decided to employ it here.

WARE: The Branford Bee strips were inspired by a painting by my art-school friend Bruce Linn called Crying Bee, which he gave to my wife and I in the late 1990s. (She and he had played together in a band briefly called Adult Entertainment.)

The use of the oval/circle template was sort of an extension of the final way I drew Quimby the Mouse in 2000, growing out of the way I cartooned the vitamin-pill-headed Jimmy Corrigan in the early 1990s (the one who looks like Stewie on Family Guy). It's also something of a parody of those "how to draw" comics from the 1920s and 1930s in which everything, apparently, can be made from circles, and which I've used as a repeating visual gag on the mind/body problem, from McSweeney's to the bee strips. At the same time, my best friend Ivan Brunetti started using an oval template in the construction of his comics, and through talking about Otto Soglow and other, more diagrammatic comics during our weekly dinners, we unquestionably influenced each other's thinking. He credits me with starting to use the template and I credit him with starting it; either way, we both sort of started doing it a lot around the same time, and have jokingly come to think of it as "The Chicago Style."(My personal name for it is the "Big Ass" style, though Ivan keeps his asses much more diminutive.)

MAUTNER: A frequent theme in your work is that of family, and how parents, especially absent or inattentive ones, can affect their children's lives in unintended and often tragic ways. While there are elements of that in Building Stories (the main character's father seems loving but distant and somewhat unknowable), there's also the main relationship between the central character and her daughter which is very positive and loving. Is this a simple maternal vs. paternal theme here or is there something else going on? How does Building Stories touch on the importance of family? Also: You became a father yourself a few years ago. How did your own experiences as a parent shape this work?

WARE: I actually hadn't thought of the two books' themes in that way, but I guess you're right; the Dad character must somehow reflect my own lack of a father for a while when growing up, though I don't think that the husband in the book, Phil, is a bad guy at all. The book is really much about how having a family shifts everything into a "before and after" sort of situation, almost a reversal of polarity or of current, when things stop flowing into one and they start flowing more outwardly. Of course, nothing happens purely and cleanly, and the main character still regrets abandoning her creative dreams -- which is, as I mentioned above, where everything ends up residing, including the book itself.

Having a family answered pretty much every question and problem I ever thought I had in life; it's made me a much better person, I think, or at least I hope it has. Though it can't solve one's problems if one isn't already somewhat stable, it can be the final catalyst towards the necessary firming up, or maturation, of the spirit (though America keeps assuring one that this is completely avoidable, if one prefers). I cringe with embarrassment when I think of my pioneer great-great-grandmother Clara F. Abbott and the privation and grimness she endured on the 1850s Nebraska prairie so I could … what? Draw comic books?

MAUTNER: I wanted to address something David Ball brought up in his Q&A with you at SPX (I didn't get to attend the panel but he emailed me some of the questions he asked): your interest in architecture and how it relates to Building Stories. On a certain level, the box itself is a building and the individual comics are rooms we "walk" though, though we're walking through imaginary people's lives instead of a physical space. This, I think, is underscored by the cut-out portfolio Drawn & Quarterly put out, where we get to assemble a replica of the building. I'm assuming this is informed by your interest in architecture — particularly the architecture of Chicago — but in what way and to what degree? And is there any way in which the "space" we move through the box relates to the "space" between individual panels?

WARE: My incessant use of rulers is more of an attempt to get at how houses and buildings affect the shapes and structures of our memories, and how these shapes can continue to live on in our minds years or decades once the buildings are gone. For example, when one comes down a stairway day after day after day, something gets imprinted on the memory and the mind about rounding a corner and grabbing a banister in a very primal, almost non-verbal way. Even though it's not an "image" exactly, that shape or the shape that movement creates is just as much a memory as how a house or a person looked at a given time, and it can shape dreams and even experiences, inducing recollections to arise at odd, unexpected times whenever a corner is rounded and a banister is grabbed. As I've gotten older, I realize that this unnamable quality is a very important and strange aspect of comics (along with a few others.)

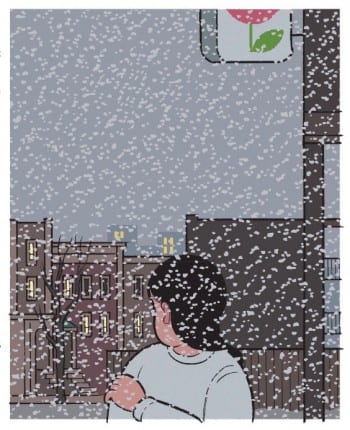

MAUTNER: Another central theme in your work is communication, or lack thereof, i.e. the way that people are unable to express their true emotions and desires to anyone but themselves. In Building Stories, especially in the "later" sections, the characters seem unable to communicate because they're constantly distracted by their iPads, phones, and other technological devices. Do you feel like technology has made true, honest communication more difficult or is that an easy out? Are we just hardwired with a certain inability to effectively express ourselves?

WARE: I tried to portray a fairly well-adjusted relationship between the main character and her husband, but it's true -- I lingered on those moments when they're staring down into their little glowing pits and not really experiencing the moment (which is simply a technological highjacking of what adults are apt to do anyway). Lately, I'm flabbergasted at the number of times I'll find myself in the exact same circumstance with my wife. Maybe there's an "app" for this.

It's the artist's or the writer's duty to try and tangle with what seems unnavigable about life as one experiences it. Though one might not produce any answers, frequently simply showing something can be useful. Human beings generally don't notice things unless there's a name for them.

Finally, one really has to credit Apple for changing the universal gesture of "trying to remember something" from looking above one's head (which is where apparently things used to be stored) to reaching into one's pocket.

MAUTNER: You recently attended the Small Press Expo in Bethesda, Md. As someone who doesn't usually attend comic conventions -- and as a first timer at SPX -- what did you make of the show? Were you able to take away any impressions at all about the aesthetic health or lack thereof of the medium?

WARE: To be honest I hardly got to see anything, as I spent most of my time behind a signing table. I genuinely like meeting people (though one girl, a friend of Dean Haspiel's, sent me a mini-comic about her being turned away from the signing line repeatedly, about which I of course felt awful, since I had no control over that and didn't even know when and where it was happening). I've said many times and I genuinely believe that there are more serious and good cartoonists working now than ever before, and I'm inspired that so many younger artists have created a world that's so welcoming and unjudgmental; it's really heartening.

I also hope they realize the incredible advantage they're operating within by not having to answer to any editors or producers or directors and that comics as a medium could ideally be the most visually honest and consciousness-plumbing medium out there, even more than film. Cartooning is profoundly personal, grueling, and potentially serious work, but there's a very steep "learning curve" to the discipline and it can't be rushed through, or tossed off. I'm most inspired by work that, as my friend Richard McGuire says, "takes chances and risks," rather than tries to sell itself.