In the twenty-first century, comics from sub-Saharan Africa have slowly begun to emerge onto the international landscape of the medium. Recent years have brought us French-language albums from Congo, Cameroon and elsewhere, South African graphic novels and Nigerian superhero comics, among others. Much attention has also been paid to political cartoons from across the continent. The Angoulême festival presented a major African comics event in 2006, and continues to host events and panels on the subject. Comics festivals are held in Lagos, Brazzaville, Yaoundé and other African cities. 1

Looking further back, however, the story of sub-Saharan comics in the first half of the 20th century -- during the colonial era -- seems a sparse and rather dreary affair. Published histories present the same few examples of newspaper strips and magazine panels that almost always reflect the racist, paternalistic attitudes of the colonialist or missionary publications in which they originally appeared3. These comics were, for the most part, created by non-Africans, and their graphic style derived entirely from European models.

And then there’s Ibrahim Njoya.

Born around 18874 in the Bamum kingdom of western Cameroon, Njoya was one of the earliest African artists to work in the medium of drawing on paper. From the 1920s through the 1950s, he drew scenes from the history and daily life of Bamum culture, often using juxtaposed images, sequential narratives, elaborately patterned framing, and innovative relations between drawn image and calligraphic text.

Njoya’s drawings were created as individual artworks, not for publication or reproduction. His work didn’t launch a “comics industry” in the usual sense of the word, and it doesn’t seem to have had a discernible influence on contemporary Cameroonian comics. Still, Njoya surely merits the designation of “premier auteur de bande dessinée d’Afrique” (first African comics creator), bestowed upon him by African comics expert Christophe Cassiau-Haurie5. Artist/critic Everlyn Nicodemus describes Njoya as “one of the first autonomous artists south of the Sahara,” linking him to the earliest movements in African modern art, “a departure from a pre-colonial functional system of visual production, a departure that may often count for a specific African dimension.” 6

If we seek a different way to consider the early history of African comics, the work of this extraordinary artist is a good place to start.

The Sultan’s Dream

The art of Ibrahim Njoya offers a window into the time and place in which he lived and worked. His career is inextricably linked to the reign of his homonymous older cousin, patron and collaborator, the visionary ruler Sultan Ibrahim Njoya. It’s worth looking at this fascinating and complex period in some depth. For clarity’s sake, while dealing with the historical background, I will refer to them as Sultan Njoya, and, for the artist, simply Ibrahim.

Beginning in the late 1890s, the kingdom experienced a surge of cultural and artistic activity, spurred by the inventive leadership of Sultan Njoya. Maneuvering between home-grown political rivals, Islamic influences from outside the kingdom, and colonial invaders from Europe, the Sultan sought to reaffirm the traditions of his people, incorporating imported ideas and technologies as well as highly creative innovations of his own.

Sultan Njoya’s father, King Nsangou, had been killed in battle, sometime between 1885-89, when Njoya was a child. After a regency administered by Njoya’s mother, Njapndunke, for most of a decade, Njoya ultimately regained the throne through victory in a civil war over succession with several of his uncles. To achieve this success, the young King took the daring step of allying with Islamic Fulbe people, who lived to the north and had been enemies of the Bamum throughout the 19th Century. Impressed by their military prowess, the King converted to Islam and invited scholars to his kingdom to teach the tenets of the faith (he also acquired horses, which had given the Fulbe a major advantage).

Though Europeans hadn’t yet reached the Bamum lands when Sultan Njoya took power, he was doubtless aware of their rapid colonial expansion. Anticipating such threats, and “driven by equal measures of intellectual curiosity and political necessity"9, the Sultan embarked on a series of ambitious cultural initiatives.

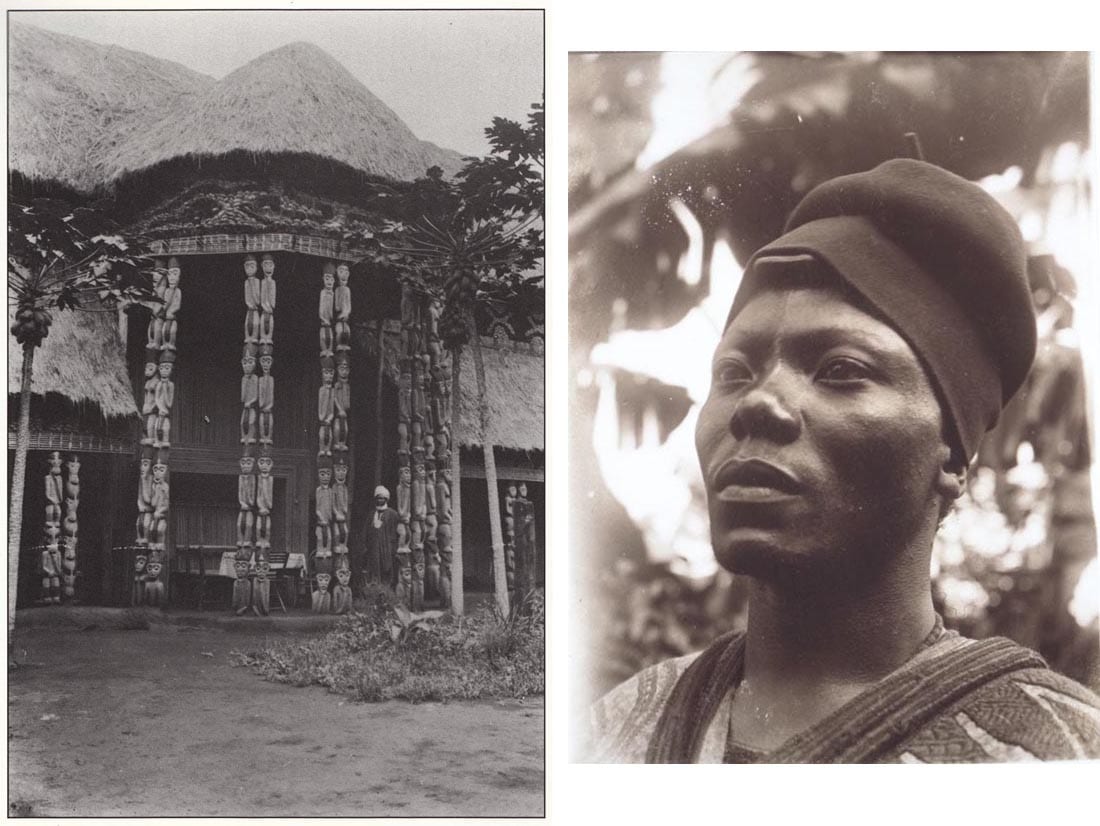

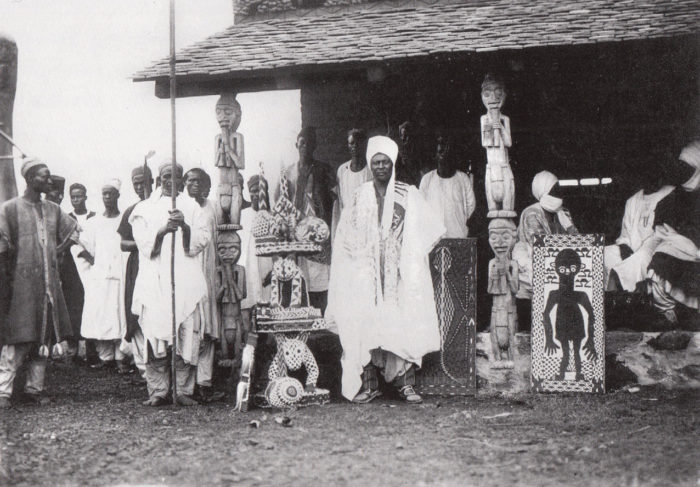

Sultan Njoya gathered around him a number of creative young nobles to help bring his ideas into reality, most notably Nji Mama Pekekue10 (1880-1954), first cousin of the Sultan and older brother of the artist Ibrahim. He rebuilt the royal palace, commissioning a facade made of closely-placed columns carved with figures, “trees of people” as they were called, modelled on the palaces of the nearby Bamileke people.11 In 1900, Sultan Njoya established workshops for young artists in various media, in close proximity to his palace.

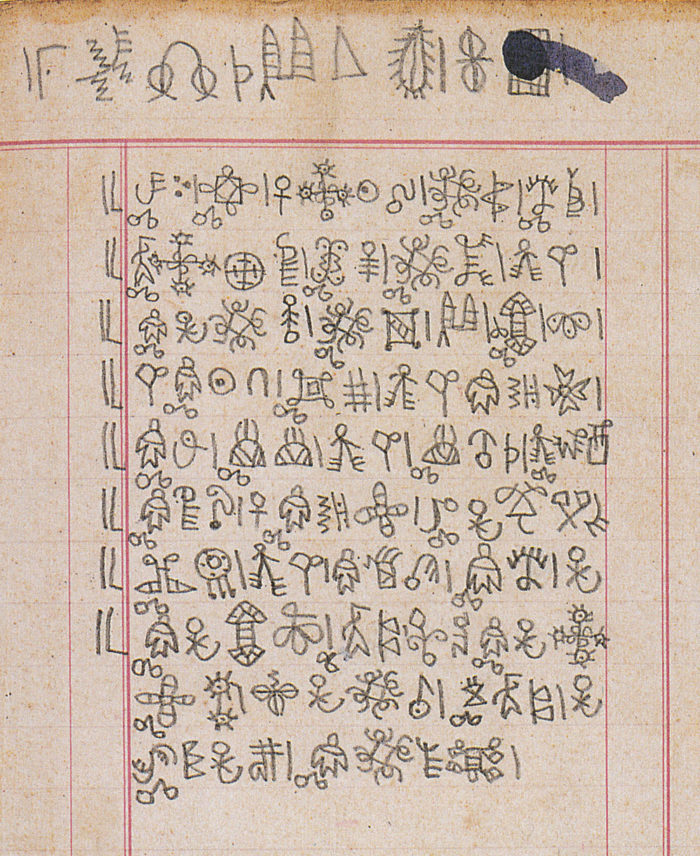

But the Sultan’s most famous innovation was an original system of writing, the Bamum script (sometimes referred to, perhaps incorrectly12, as the “Shü-mom script;” Shü-mom refers instead to a secret court language that the Sultan also invented!) In the mid-1890s, shortly after assuming the throne, Njoya decided - based, he said, on a dream - that his people needed a writing system of their own, distinct from the Arabic or European alphabets. He commissioned a pictographic alphabet, initially comprising as many as 1000 characters.13 This first version, completed by 1896-1897, is known as the Lewa script; one of its principle designers was Nji Mama. Eventually, a version of the Bamum script was used for official court documents, and for historical, medical and religious writings. Sultan Njoya would open royal schools to teach the script, as well as Bamum history. At its peak, the alphabet would have as many as 1000 literate users.

These actions by the Sultan would have a major impact on Bamum graphic art. As Cameroonian writer Patrice Nganang points out, Sultan Njoya’s invention of the Bamum script had initiated a new form of writing that is “related to… drawing, in a very intimate way.”14

In 1902, German colonizers arrived in the Bamun Kingdom. The entire region had been claimed by Germany in the European “partition” of Africa in 1884. Resistance by neighboring peoples had proven futile, so Sultan Njoya opted for a tactical surrender, warmly welcoming the German occupiers. This strategy allowed the Sultan to maintain a high degree of autonomy in his administration of the state: he ceded military authority to the Germans, but was able to continue his ambitious cultural projects without interruption, while also seeking to modernize and reform his kingdom. The Sultan also welcomed Protestant Christian missionaries from the Basel Mission, who established a base in Foumban in 1906.15 He encouraged his nobles to enter their children in Christian schools, while still maintaining his own Bamum schools.

Ibrahim the artist

The younger Ibrahim Njoya was the son of a half-brother of the Sultan’s father. At an early age, his artistic talent was noticed in drawings of figures traced in the sand with his friend Mama Kwandu, one of the Sultan’s sons, and in murals he painted on the walls of his older brother’s home. Starting at age ten, he attended one of the Sultan’s schools, where he learned the then-current version of the Bamum script. While still in his teens, Ibrahim Njoya was hired as a personal secretary to the Sultan. In 1908, the Sultan made Njoya director of a new school in Foumban. He rose quickly to become one of the Sultan’s closest advisors, serving as the royal treasurer from 1912 to 1920. 15

Ibrahim attended the Protestant missionary school and was baptized in 1910 (for a time he adopted the Christianized name Johannes Yerima), though he returned to Islam in 1916.16 He translated Biblical texts into Bamum, and decorated these pages with geometrical designs.17 He also contributed original batik designs in the textile workshop that the Sultan established in the palace18.

The Sultan's palace had been destroyed by fire in 1913, and Ibrahim oversaw the construction of a new one, beginning in 1917. This was an architectural tour-de-force that incorporated the skills of the Sultan’s finest court artists - including Nji Mama, Ibrahim and the master carver Amadou Mfunsie. It was completed by 1923.19

Having recognized Ibrahim’s graphic talents, the Sultan put Ibrahim in charge of a 1910 revision of the Sultan’s Bamum script. The original, pictographic version had proved unwieldy, and had been gradually reduced to 286 characters. Ibrahim’s version transformed the ideographic signs into a functional, 80-character syllabic alphabet, (also known as the a ka u ku script, after its first four characters).

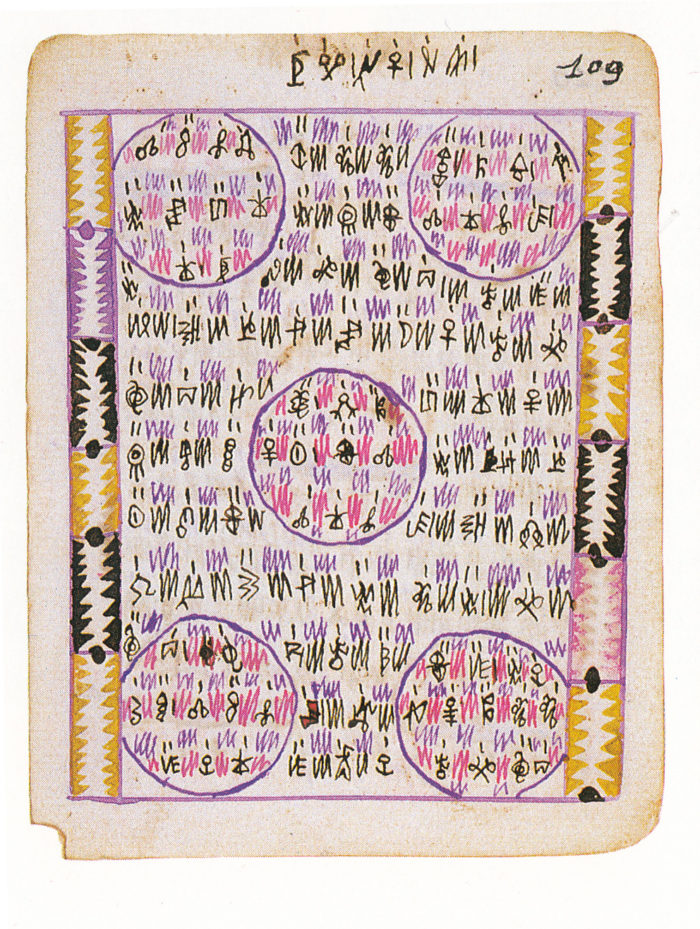

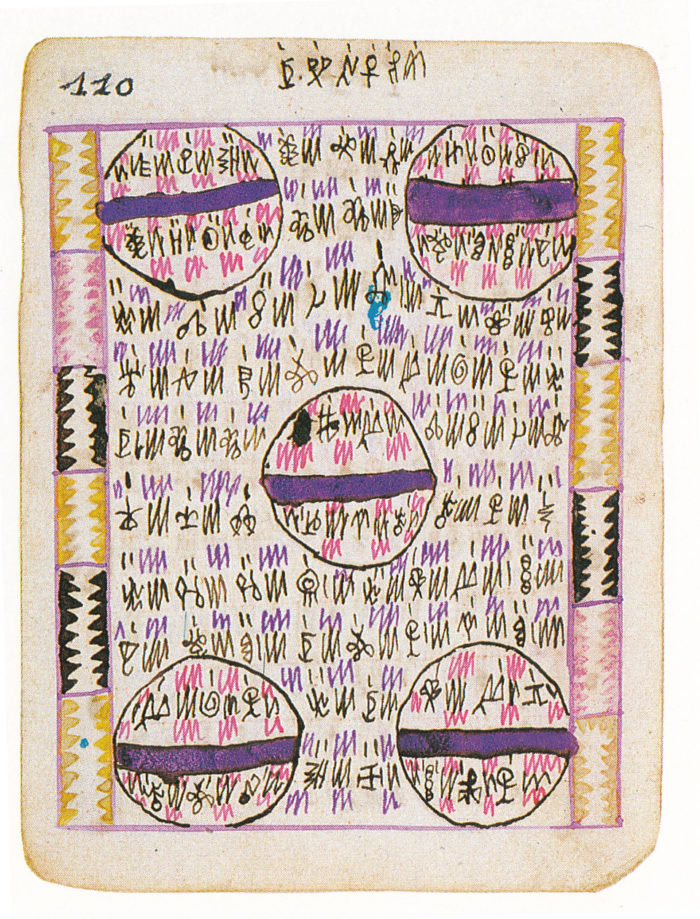

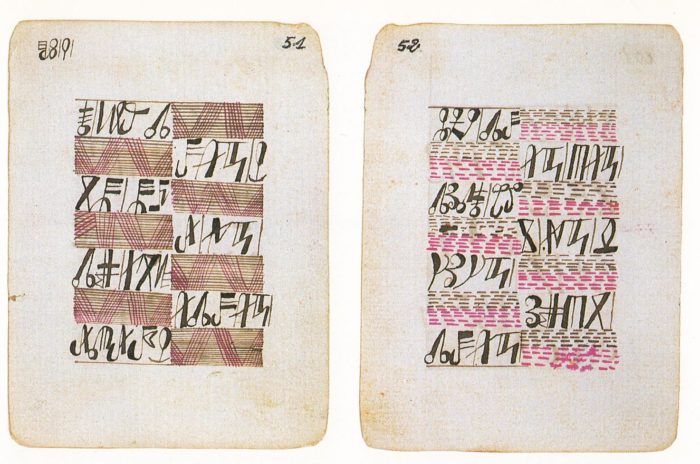

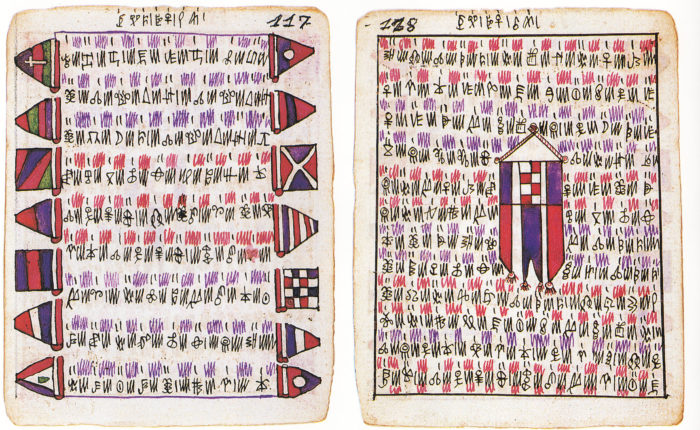

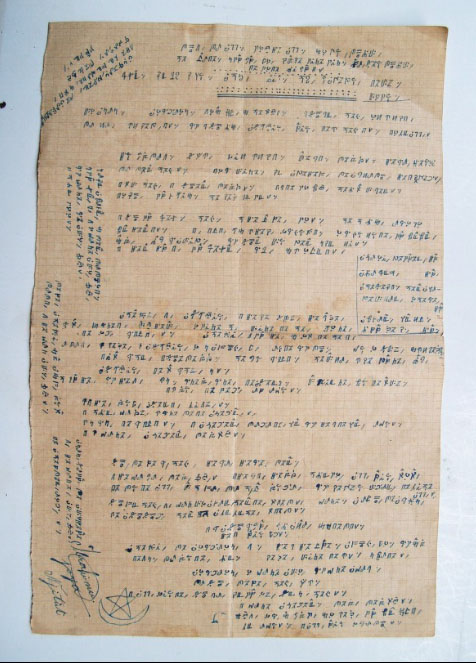

In 1916, Ibrahim designed and lettered the Sultan’s book “Nwet Kwete” (Pursue to Attain), which laid out the precepts of another ambitious project, his own syncretic religion, which blended elements of Islam, Christianity and Bamum spiritual beliefs.21 Ibrahim’s pages are strikingly composed and feature an exciting play between abstract design elements and the hand-drawn calligraphic text. Pages 51 and 52 integrate the Bamum lettering with colorful patterns, hatching and dashes.

Later the layouts are even more dramatic, adding patterned borders and segmenting the page into circular panels that seem to punctuate the flow of the text (pages 109-110), or enclosing the entire text in a circle, surrounded by a segmented colored border (pages 95-96). In pages 117-118, flag-like emblems adorn the text, in the borders or incorporated into the page (118). With its blending of text with design elements, Nwet Kwete appears to be a hybrid visual/literary document, its specific layout and graphic character integral to its message.

New Media

Sultan Njoya’s Bamum script project also introduced Bamum artists to a new medium, drawing on paper. 22 Paper, pencils and india ink were not produced in sub-Saharan Africa prior to the colonial period. Before this, drawing was practiced in the Bamum kingdom as a means of sketching designs for masks, sculpture and architecture, and had been executed on various media: charcoal on wood or stone, or designs etched into clay or burnt into wood or bamboo (the first version of Bamum script was written on wooden boards). Two-dimensional design and imagery was also an element of pre-colonial Bamum art, in textiles, carved wooden doors, as well as tattoos.23

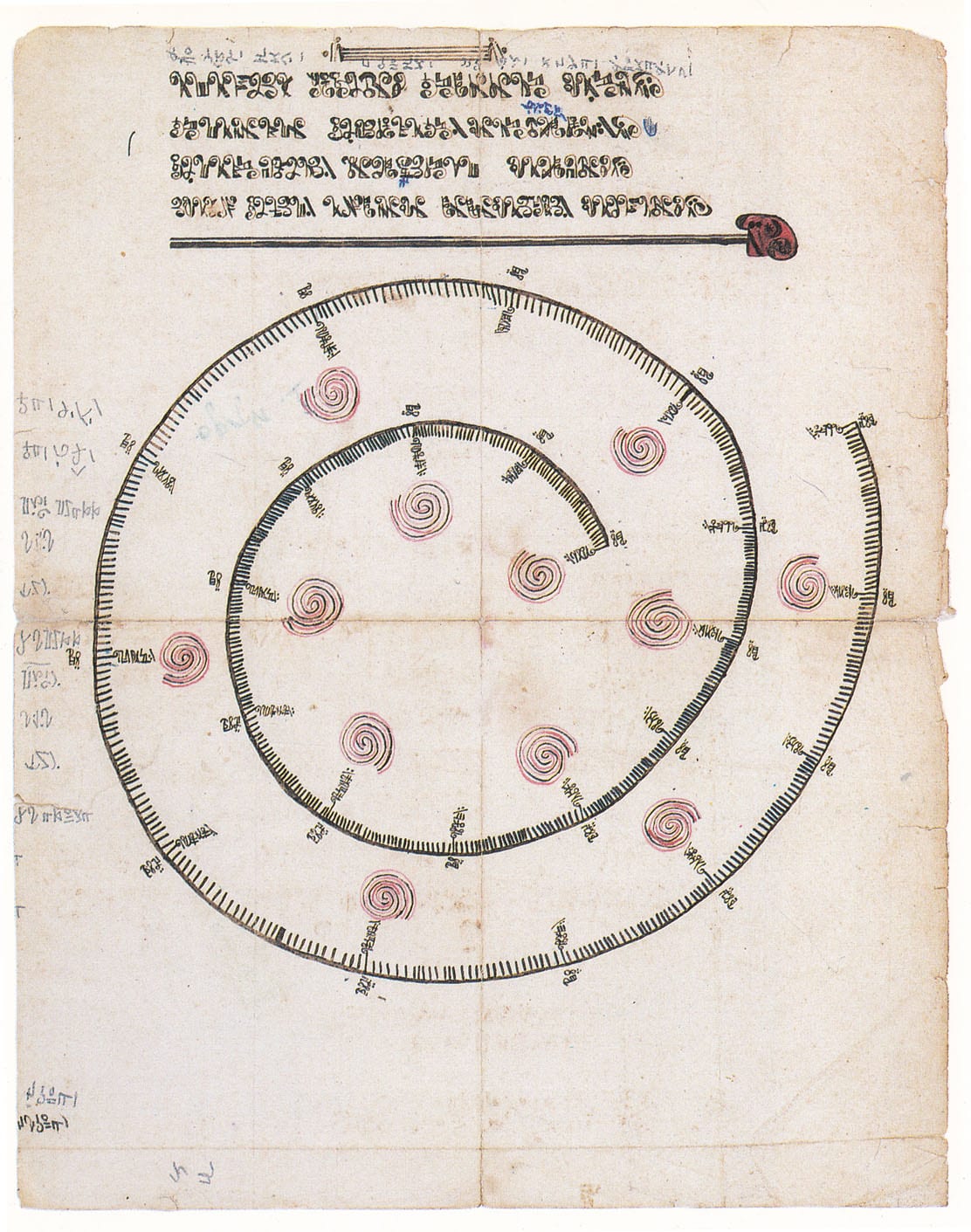

The graphic skills and techniques honed in the development of the alphabet and the creation of books like Nwet Kwete, were soon applied to representational drawing, establishing a relationship between text and image from the outset.24 The development of Bamum script thus facilitated the growth of drawing as a distinct art form, which was still quite rare in Central and Western Africa at that time.25 Ibrahim’s first figurative drawings were produced during his early years of service in the palace, though most of these early works were lost in a palace fire in 1913. Drawing was taught at the palace school that Ibrahim directed starting in 1908. 26 The new medium resulted in other possibilities as well, including cartography.27 Nji Mama drafted the first Bamum maps, but Ibrahim would reproduce his own versions often.

Changing Colonial Situation

The First World War had major consequences for the Bamum state. In 1916, as Germany’s fortunes faded, the kingdom fell under French colonial rule. Sultan Njoya’s accommodating strategy was doomed to fail against the new occupiers, as the French were much less “indirect” in their management of colonial possessions, and frowned on independent local rulers. France aggressively pursued the “Gallicization” of their colonial subjects, instilling French language and cultural values that would inevitably clash with the autonomy the Sultan had enjoyed under the Germans.

This process was hastened by political conflicts within the Bamum nobility itself. A member of a rival branch of Sultan Njoya’s family, Mosé Yeyap, who worked for the French as a translator, sought to weaken the Sultan’s position from his position within the colonial administration. Yeyap was a Christian, educated in the Basel mission school, fluent in German as well as French.28 Prior to the arrival of the French, he had served the Sultan in various capacities, but under the new colonial regime he would become a formidable antagonist to the monarch, in the realms of culture, religion and politics.

Beginning in 1919, the French instituted a number of policies that disrupted the economic order supporting Sultan Njoya’s political powers and resources. These include the elimination of Bamum systems of slavery, polygamy and tribute payments. Later in that year, based on trumped-up conspiracy charges, the Sultan and several of his close associates were exiled to Campo on the Cameroonian coast. Ibrahim was among those joining the Sultan in exile,29 though here seems to have been some ambivalence in the the French authorities’ view of him. One official report described Ibrahim as one of ‘deux conseillers intimes du KING accusés d’avoir sur lui la plus mauvaise influence” ("two close advisors to the king accused of having the worst influence on him"). Elsewhere, a lighter deportation sentence was recommended for Ibrahim who could “bénéficier d'une certaine indulgence” ("be granted some leniency").30 The exile lasted a little over a year year.

The Two Museums

Sometime in the 1920s31 Mosé Yeyap opened Foumban’s first museum to display the work of Bamum artists. Situated at some distance from the palace, in the vicinity of the French Protestant mission, the museum included many objects from Yeyap's own collection, including some with significant connections to royal power.32 Born of the political rivalry between Yeyap and the Sultan, the new institution also reflected a transformation in the meaning of art and the role of the artist which would take place across Africa under European influence.

The Sultan employed his artists and artisans to provide objects which supported, symbolized and glorified royal prestige, as well as for the secret societies which formed part of the kingdom's power structure.33. This had been the role of the arts since before the coming of the colonial powers: “things [i.e. art objects] played a major role in processes of state formation and consolidation, communicating in aesthetic terms the political charter underlying the Bamum polity.”34.

In contrast, Yeyap’s museum presented the work of Bamum artists in the context of an incipient international market for “traditional” African art. Though the Sultan had instituted some reforms, allowing certain types of object to be created outside of a court system, Yeyap's aims went farther, and this view of art as aesthetic and commodified objects was far more compatible with the colonial system.35 African art was redefined in ethnographic terms in which concepts of the traditional, the "native" and “authenticity” were greatly privileged: Yeyap went as far as to stage ersatz “rituals” in which newly produced art objects were used, essentially a marketing scheme to make the objects more desirable to Western collectors.36

The Sultan responded, eventually, by opening a museum of his own in the Palace itself, where the public could view sacred and royal objects -- the “things of the palace” which carried great symbolic meaning as the emblems of traditional royal power. The Sultan’s museum can be seen as a capitulation to new conditions: "the king’s resources were reduced to a series of possessions for which he could act as curator.”37

Thus, two factions in a pre-existing Bamum political conflict mobilized concepts of art, economy and power into the ongoing struggle: “What the colonial administration saw as the loss of royal prestige and secularization of a sacred art, Bamun considered a political struggle."38 The outcome, though, would be determined by the asymmetrical power of the colonial occupiers.

Both museum’s still exist today: Yeyap’s would eventually become the Musée des Arts et Traditions Bamoun, and the royal palace still houses the Bamum Palace Museum.

The Sultan’s Fall

The conflict between Sultan Njoya and Mosé Yeyap came to a head in May, 1924. Recent French decisions had further diminished the Sultan's power, when a group of regional chiefs had been appointed to exercise what remained of local authority and the Sultan's income was reduced to a relatively small allowance from the colonial government, which he complained was insufficient.39 When an armed crowd of the Sultan’s supporters demanded that French authorities remove Yeyap from his official post, the administration sided with Yeyap, stripping Sultan Njoya of all governing powers outside of the palace. This essentially ended the Sultan’s reign over the Bamum kingdom.

The Sultan was no longer able support the artists’ workshops around the palace. Yeyap, with the French administration’s approval, established a new center for artists' studios and shops, the Rue des Artisans, far from the palace, solidifying the transformation of Bamum arts into a commodified, market-based phenomenon.40

Yeyap is in many ways the “villain” of the story, complicit in bringing down the compelling figure of Sultan Njoya. But Yeyap's efforts, though no doubt motivated by political rivalry with the Sultan, might also be seen as an alternative approach to cultural adaptation and survival under colonial rule: he helped to develop a market among colonial occupiers and visitors for the artistic productions of Bamum artists, allowing the artists to make a living.41 Yeyap offered the French a victory by removing the “pagan” power of Bamum arts and rituals and transferring them to Christian, colonial terms -- removing the arts’ role in supporting traditional power structures. At the same time, though, he was integrating Bamum artisans into the new reality of the colonial capitalist economy, which could not, at the time, be defeated, and whose legacy would continue after the colonial era.

Of course, the Sultan's loss of power and prestige through the 1920s meant that the dissemination of the Bamum script, opposed by the French, was ultimately abandoned. A Bamum alphabet printing press, which Sultan Njoya had made by his court artisans, was never used; the Sultan ultimately destroyed in his frustration over the colonial government's defeat of all his plans.42

In 1927, Ibrahim won first prize in an international art contest with a depiction of the battle of Manga, which had confirmed the Sultan’s reign some 40 years earlier. This prize must have had great importance for the artist, since he mentioned it in an interview with historian Claude Tardits, many years later. From this point, Ibrahim’s drawing output increased; his depictions of historical and traditional scenes were sought after by collectors, especially wealthy foreigners who resided in the Bamum kingdom during the colonial occupation.43

Ibrahim also returned to calligraphy and book design, helping the Sultan to complete a major work of history and memoir, the Sang’aam, also known as the Histoire et coutumes de Bamum. The front and back cover designs show another side of Ibrahim’s graphic talents, reminiscent of European modernist graphics of the period. Figurative elements are arranged in geometrical configurations to combine abstract design, imagery and text, intertwined in the same composition.

In 1931, Sultan Njoya was forced into a final exile, this time in the capital, Yaoundé. He died there in 1933 feeling disillusioned and betrayed by his own people. As he wrote in the Sang’aam: “What kind of people are those who love somebody only when they have been sufficiently fed by him? And even after being fed by you, they still don’t really love you. In fact, they take you for an imbecile. And if you don’t give them enough gifts, for them you are a bad person. The Bamum? What kind of people is that?”44

With the Sultan out of the picture, the French colonial authorities had no further use for Mosé Yeyap. Though Yeyap had successfully maneuvered to undermine Sultan Njoya’s royal power, he would fail in his attempts to dismantle the Bamum dynasty altogether. The French saw some benefit in keeping the traditional sovereignty intact, at least symbolically, and installed a new sultan, Njoya’s son, Seidou. Yeyap was “gradually sidelined from the affairs of the kingdom”45and ultimately removed from his position in the colonial administration, years before his own death in 1941.

Ibrahim’s career after Sultan Njoya’s Reign

Sultan El Hadj Seidou Nimoluh Njoya’s power was mostly symbolic 46, but his long reign brought cultural stability to the Bamum people through the remaining decades of French occupation and well into independence. Ibrahim Njoya was the preeminent artist in the kingdom, the leading figure in a “school” of Bamum art which thrived for decades (referred to as “Njoyism” by educator and critic Natty Mark Samuels).47.

Njoya’s drawings and other works, taken as a whole from the years of Sultan Njoya’s decline onward, offer a multifaceted representation of Bamum history and culture. Annette Schemmel describes his work as an example of “auto-ethnographic rendering,” in which the artist portrays the identity of their culture at a moment when it is under external pressures from the encounter with European power.48

Does that interpretation reflect a Western bias? Patrice Nganang questions looking through a “global paradigm," which defines and organizes African literature through the prism of colonialism, instead of a one of African artistic identity. “The independence of African countries from Europe in 1960 becomes a turning point in the many-thousand-years-old intellectual history of the African continent," he writes, "only because of the global paradigm through the frame of which that history is read.”49

In the following examination of Ibrahim Njoya's artworks, I'll try to avoid this paradigm and limit my analyses to the admittedly Western, but narrower perspective of comics form.

Battle scenes are one of his frequent subjects, as well as the so-called “kings list” drawings, which display Bamum rulers in sequenced order, often incorporating other scenes or images as separate panels. Njoya was able to execute repeated versions of these themes on commission, basing them on precise pencil sketches which served as templates.50 Ink, watercolor and colored pencils were used to finish the individual works.

One of the most striking elements of Ibrahim’s drawings is his use of patterning, especially within his elaborate ornamental borders. Some of these patterns are associated with Bamum royalty, probably derived from textile designs. The borders function both as ornamentation and an addition to the complexity of the artist’s narrative systems, as an “independent code of interpretation,"51 with particular patterns and animal imagery carrying specific cultural significance.

The “kings list” compositions may have been partly inspired by German propaganda and memorabilia which presented portraits of Kaiser Wilhelm and his family arranged in vignettes or panels.52 But where the German versions are stiff and formal, Ibrahim creates dynamic interaction between lively portraits of the kings, their heads inclined at diverse angles, gazes leading in different directions; we half-expect these former monarchs to start debating each other over whose reign was greatest.

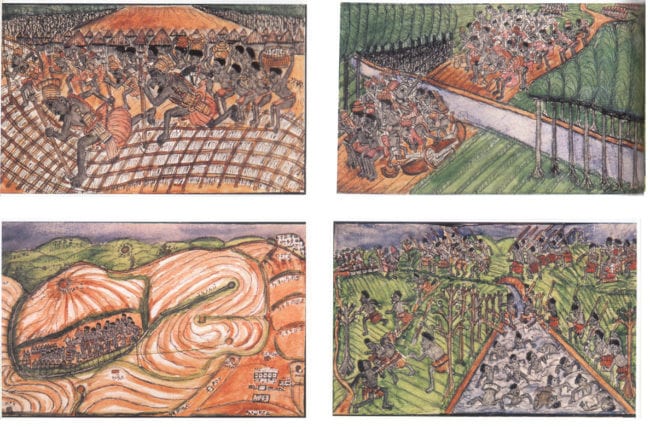

In Portraits des 18 rois bamum Bataille de Manga contre Gbèntkom Ndombuo [Portraits of 18 Bamum kings / Battle of Manga against Gbèntkom Ndombuo](c. 1938-1940) Njoya combines a king’s list page and a battle scene into one multi-panel work that incorporates numerous visual systems into a complex narrative of history, genealogy, daily life, animal mythology and symbolic patterns. The king’s list page, on the left, vibrates with patterns and images: the 18 portraits are both sequential and hierarchically scaled, with Sultan Seidou in the center, largest panel. Four additional panels on either side of Seidou depict activities such as farming, hunting and dancing. Below, a fifth panel presents Sultan Njoya teaching the Bamum script. The border contains decorative patterning punctuated by repeated panels of two significant animal images: the two-headed snake, a symbol of the Bamum kingdom, and a spider, symbol of wisdom and of connection to the spirit world.

The right hand page features a panoramic drawing of the battle of Manga. Unlike in the earlier depiction of the same event, Ibrahim has now begun to make use of perspective, with the figures in the background smaller than those in the front. We see in the top center of the page the Fulani cavalry that was key to this important military victory. Sultan Njoya, on horseback as well, slays one of his enemies in the lower center of the page. The border around the battle scene is particularly complex, made up of individual panels depicting traditional activities and, along the bottom, animals. Small central text boxes are contained in the lower border as well, on both pages.

By combining the two themes, the "kings list" and the battle scene, Ibrahim creates a historical narrative without fixed reading order. As our gaze moves back and forth between them, the battle on the right (in which the young Sultan defeated his father's enemies to affirm his right to the throne) has an implied chronological place in the sequence of kings on the left: in the “gutter” between the panels of Sultan Njoya’s father and the Sultan himself. But the battle image also underpins the entire narrative of the "kings list" page, since it depicts the victory that sustained the dynasty. Woven around and through the dominant images of Great Men and martial spectacle, the smaller scenes of activities and animal imagery remind of the daily life of the kingdom.

Cultural self-portraits

In a different genre, Ibrahim created several works that explicitly "catalog" different aspects of Bamum culture. Several of these works are in the collection of the Ethnographic Museum of Geneva, to which they were donated by Jean Rusillon, a missionary formerly stationed in Foumban. Rusillon acquired the pages between 1929 and 1932, which is thought to be the period in which they were created. These pieces aren't signed, but they are confidently attributed to Ibrahim by Claude Savary of the Geneva Musuem, among others.

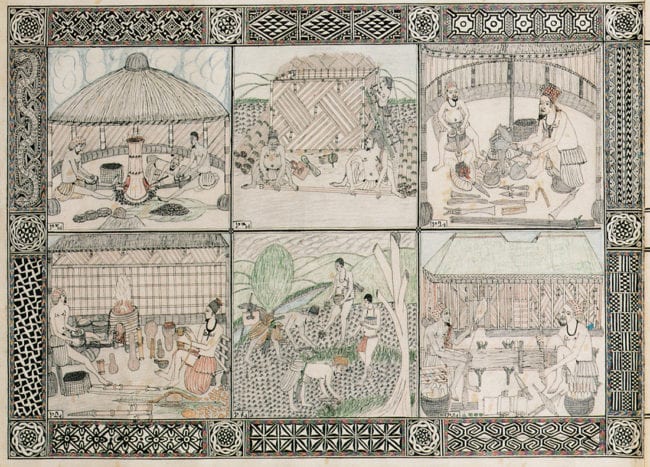

Planche des artisans [Page of Artisans] (1929-1932) consists of 12 panels, arranged in two six-panel grids surrounded by patterned borders and separated by two text-boxes, which explain the images (in Bamum script). The panels are ordered left-to-right and top-to-bottom, across the entire page. Each panel depicts Bamum people engaged in a different craft or work activity -- iron-working, farming, house-building, farming, basketry, etc. Njoya stages the artisans’ activities in appropriate locations, with their materials and tools clearly depicted, so the whole gives us a detailed overview of traditional daily economic life, presented at an historical moment of rapid change in Bamum society and culture. The text tells us that these are crafts practiced by the Bamum before the whites had arrived, and that the characters depicted are portraits of "well known" people, "but many others in Foumban know how to do similar work."53

Planche des objets [Page of Objects] is one of Njoya’s most celebrated pages: a ten-panel composition of inanimate objects linked to Bamum rituals and royalty. Superficially, it bears some resemblance to European encyclopedic illustrations, but, as with the "kings list" pieces, Njoya infuses this “catalog” image with life, through his use of diagonals, patterns and varied distribution of objects across the page, as well as soft, warm coloring.

The cultural narrative contained in this presentation of "things" operates on multiple levels. The objects depicted were those housed in the royal palace -- and subsequently the palace museum -- and thus have political historical, and even sacred significance.

Different groupings of objects are associated with different rulers: Sultan Njoya’s linguistic and literary endeavors are symbolized by the alphabet and books contained in the boldly outlined panel at the far right. This image may have been commissioned during the Sultan’s exile in Yaoundé, for Mosé Yeyap’s museum, part of a general colonialist effort to de-mystify and “museum-ify” the traditional emblems of Bamum authority. Schemmel suggests an alternate reading: as she points out, Njoya arranges all the royal regalia around a central depiction of the ntieya cloth, in which the kings were buried; the only un-captioned object on the page and an evocation of the presence of the exiled Sultan himself.54

The Planche des motifs décoratifs [Page of decorative motifs] is another in this “cultural catalog” genre, in this instance a thirty-panel grid of patterns and stylized animal imageries used in Bamum textiles, sculpture and bead work. Beyond their decorative function, these designs, most of them based on animal references, carry specific cultural meanings with regard to social ranks, royal power, religion, etc. Text boxes beneath each panel identify the pattern, its meaning and usage.55 Like many of Ibrahim’s other multi-image pieces, this composition of abstract patterns serves as a documentation of Bamum tradition; in this case, it’s also a sort of meta-artwork, a pattern of patterns, a picture (or comic) about pictures.

In a two-panel narrative drawing, Njoya presents two dramatic moments of Bamum domestic life: in the first panel, a woman gives birth to a baby, and in the second, the mother looks on lovingly as her son is circumcised. Without text, this is a pure visual narrative, bustling with activity. Strong diagonal shapes and compelling expressions lead the viewer’s eye back and forth across the gutter. A central diagonal runs from the newborn baby in panel one, to the mother’s face in panel two, focusing us on the interaction between mother and child in the second scene, as much as on the action of the circumcision. This simple line drawing may be a sketch used by Njoya to recreate the sequence for commissions or for a carved frieze; no finished versions have been reproduced, as far as I know. Reproduced in Claude Tardit's L'Histoire singulaire de l'art bamoun, the drawing's dimensions and media are not indicated.

Fables and History

When Ibrahim turned to adaptations of Bamum fables and history, his technique most closely approximated that of Western comics. Three of these, The Tale of the Leopard and the Civet, The Tale of the Frog and the Kite and The Tale of Mofuka and the Lion are held at the Ethnographic Museum in Geneva. Vertical pages, featuring sequential narrative panels within decorative compositions, the fables are softly colored in colored pencil, with black and white inked borders.

The Tale of the Leopard and the Civet (c. 1930) Ink and colored pencils on paper, 315x490 mm. A leopard recruits a civet to look after a billy goat it has caught as prey, then reurns and demands that the civet also owes it the kids that the billy goat would have given birth to. At a tribunal of all the animals, the leopard is tricked by a clever antelope into admitting that a billy goat can't give birth. 56 Source: Musée d'ethnographie de Genève

Tale of the Frog and the Kite c.1932 Ink and colored pencils on paper, 315x490 mm. In this tale, a Kite presumes on the hospitality of a Frog, knowing that it will never have to return the favor, since its host will never be able to visit its own lofty home. The frog tricks the Kite by gluing feathers to its body, pretending to be a baby chick. The Kite grabs the Frog and brings it back to its nest, where it reveals its true identity.57

Tale of Mofuka and the Lion c.1932 Ink and colored pencils on paper, 315x490 mm. For removing a bone from his throat, a Lion gives Mofuka the gift of being able to understand the language of animals, but warns him that he will die if he ever reveals this secret. When Mofuka laughs at a joke between two chickens, his wife and mother-in-law think he's laughing at them, and nag him until he admits the secret. Mofuka dies instantly, and the Lion gets revenge by killing Mofuka's wife, mother-in-law and child.58

In each, five and four image panels, respectively, are arranged around a large central text panel, and surrounded by geometrically decorated borders, which also feature small panels of animal heads at the corners and mid-points. In the border of The Frog and the Kite a regular geometrical pattern weaves around images of cowrie shells (which were used as currency in many pre-colonized African societies); Mofuka and the Lion’s border contains six different patterns separated by punctuating cow-head panels. Text is also present within the pictorial panels: small captions at the bottom of each panel in Mofuka and the Lion, and, in The Tale of the Frog and the Kite, multiple text boxes within each panel that suggest the possibility of “word balloons,” though without access to a translation we can’t be sure. Also intriguing is the notations (“a,” “b,” “c,” etc.) assigned to characters in Mofuka and the Lion, an unusual type of image-text narrative device.

The little rat, protagonist of the story, is not visible in the last seven drawn panels, but is nonetheless a strong presence, “seen” in its effect on the human characters, an unusual and “comics-specific” bit of visual storytelling.

The text of the fable is presented in vertical captions on the left side of each panel. The format of explanatory text-boxes accompanying each panel was the norm in European comics through the 1920s; whether Njoya had seen such comics is unknown, but his placement of the text panels is an interesting variation, one which has a definite effect on the reading pattern: the text precedes the image in left-right order, so the viewing eye is not required to move up and down in each panel between picture and text, but can move along the horizontal tiers in a continuous left-right motion. The text panels create vertical bars running from the top to the bottom of the page, a striking effect, at least to an eye accustomed to horizontally placed captions.

This is the most elaborate of Njoya’s sequential narratives, with numerous characters and scenes, and his narrative breakdown shows a comfortable mastery of the form. In terms of panel transitions, the first two panels show the baby rat falling behind its family, and then, in a different scene, being helped across a river by a passing trader. Panel three is the only instance of “cross-cutting” in the story, as Njoya “cuts back” to the mother rat and remaining children continuing on without the runt, across the river and out of the narrative for good. From here, the tale progresses linearly, mostly scene-to-scene, to use Scott McCloud’s terminology, for the baby rat’s various encounters. The pacing of the story slows for three two-panel sequences that show actions in the same location (panels 5-6, 8-9, 13-14).

Njoya again used a horizontal grid format (three-by-three, nine panels) for a chronicle of ancient (and probably mythical) Bamum history, the people’s migration from Syria and Egypt. Dating to sometime after the end of World War II,59 this piece raises many questions. The version that is reproduced is a partially-inked pencil drawing, perhaps either an unfinished project, or a template for finished works. Unlike in virtually all of Njoya’s finished drawings, there is no border. Text beneath each image is written in French and the panels are numbered in Western style; the narration under the first panel exceeds the space seemingly alloted for it. There are also penciled notations in Bamum script, in what are either wide gutters, or additional, vertical text-boxes as in the rat fable. Was Njoya planning, or did he complete, versions in both Bamum and French, perhaps for commission? Does the story finish in panel nine, or were more pages planned? Hopefully the answers to these questions are out there, and will come to light!

Carved comics

In the post-war years Ibrahim became a master sculptor in wood as well. Carved furniture and other objects found a lucrative market among international visitors, wealthy Cameroonians and for public buildings in Foumban. Claude Tardits links the development of carved friezes for windows, furniture and wall panelling to the progress of narrative and decorative drawing that Ibrahim had pioneered in the '20s and '30s.60

In a carved table from 1946-47, we see that Ibrahim employed the format developed in his drawings, of juxtaposed narrative images. The table’s imagery is arranged in three horizontal tiers: scenes of traditional Bamum culture -- hunting, dance, battle -- with portraits of major rulers at the corners (Sultan Njoya at lower left) and then-current Sultan Seidou in the center. Within the three tiers of the image, panel shapes are carved into the wood, though compared to the grid-based drawings, the space is more abstracted and continuous.

The piece that may have been Njoya’s most ambitious narrative drawing is unfortunately not available for viewing or study, at least not in its entirety. At some point in the 1940s, Njoya created a large, multi-panel narrative of the epic Bamum “origin story,” the founding of the state by the first King, Nchare. Claude Tardits reports that this work consisted of twenty-five water-colored panels of 18 by 11 cm each, framed together at 1m by 60 cm (presumably a five-by-five panel grid). Tantalizingly, Tardits only reproduces a few individual panels from this piece which is held in a private collection, and for now we can only imagine the full composition.61

Outside the realm of art, Ibrahim Njoya did important work after the war in documenting and preserving the kingdom’s history. He was a founding officer of the Bamum Academy, established in 1944 by Sultan Seidou. “It is necessary to clarify our history,” he is quoted saying in the minutes from an Academy meeting, “because the youth of today and the future won’t be able to.”62 Ibrahim translated historical documents from Bamum script, and made significant contributions to Claude Tardit’s comprehensive history of the Bamum kingdom, Le royaume bamoun, providing a great deal of the information and insights that exist today regarding Sultan Njoya’s court and other aspects of Bamum history. 63 In 1962, during the first years of Cameroon’s independence, Ibrahim Njoya died.64

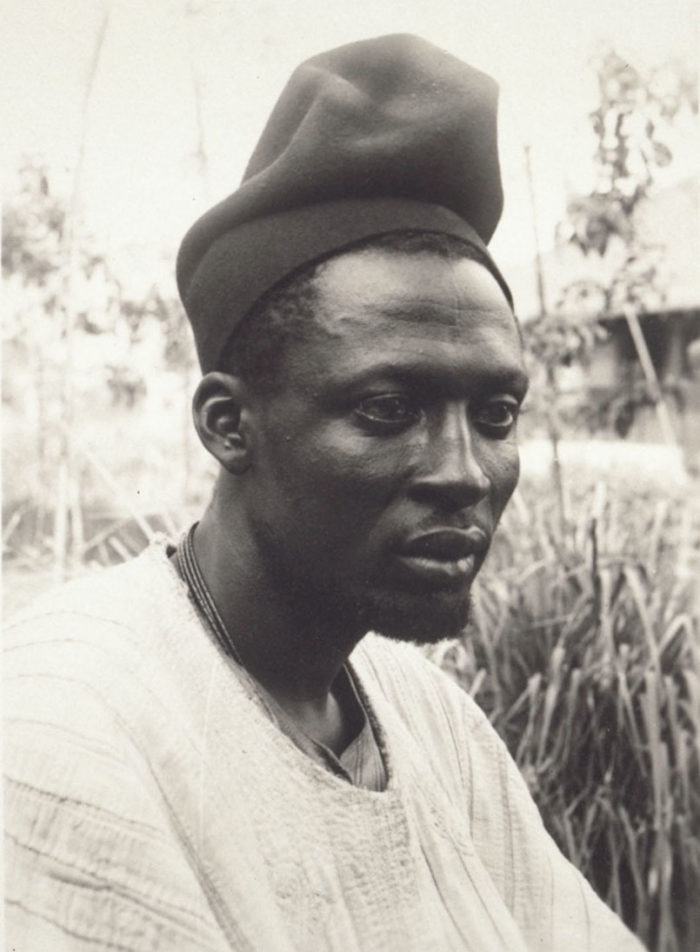

But what kind of a person was Ibrahim Njoya? While Sultan Njoya left behind a memoir, to go with numerous descriptions and evaluations of him by colonial officials, the inner life and personality of Ibrahim the artist are far less accessible to research from a Western perspective. There are no published writings. Several letters between Ibrahim and his brother Nji Mama are in the collection of the British Library, but they are written in Bamum script, still untranslated -- though efforts are currently underway in Foumban to revive and teach the Sultan’s alphabet. Ibrahim seems to have been a devout Muslim (one letter is summarized as “regarding the reason why the name of Allah should be evoked at both the beginning and the end of any social event” ),65 but besides a few such tantalizing clues, from our vantage point, the character of Ibrahim Njoya remains mostly a mystery.

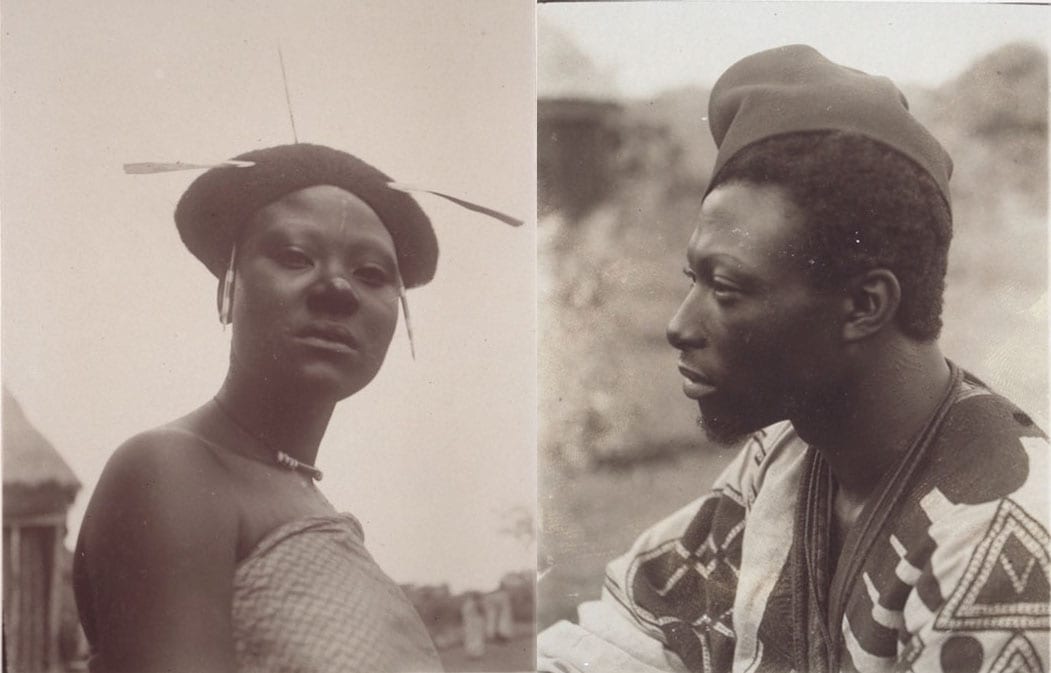

Cameroonian writer Patrice Nganang’s evocative novel Mount Pleasant, about the last years of Sultan Njoya’s life, contains a brief, vivid description of Ibrahim, as seen through the eyes of his lover and future wife, the Sultan’s daughter, Nji Mongu Ngutane , a major character in the book. Looking at the elegant photographs of the artist as a young man, I like to believe that this fictional imagining brings at least an aspect of Ibrahim Njoya, the person, to life.

The setting is Yaoundé, where the ailing Sultan is exiled, with his daughter and other members of his household there to tend to him. Ibrahim arrives from Foumban, where he has stayed behind to look after the Sultan’s interests:

The arrival of Ibrahim, Nji Mama’s younger brother, shifted Njoya’s perimeter somewhat. Although not part of the princely nobility... that man had, as he put it, abandoned the plebes and their foolishness. In short, that man, who broadcast his aristocracy through the tilt of his hat and catlike eyes, infused new life into Ngutane’s veins. It seemed that she chose her wardrobe just to garner one of his winks. … The dance had returned to her step, just as when she was in her glory, back in Foumban. If until then she had found no partner who could keep up with her, in Ibrahim she suddenly had a man whose sense of style revealed a vanity beyond compare.66.

All scans of Ibrahim Njoya artwork are from Les dessins Bamum, Musée d’Arts Africaine, Océaniens, Amérindiens, Marseilles, 1997, unless otherwise noted.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bena, Timba “Njoya o la invención de una modernidad africana” LĖpan África Revista. Agosto-septiembre 2018

Bumatay, Michelle Sub-Saharan African Francophone Comics http://professorlatinx.com/comics/sub-saharan-african-francophone-comics/

Cassiau-Haurie, Christophe http://bdzoom.com/64560/patrimoine/hommage-a-ibrahim-njoya-premier-auteur-de-bande-dessinee-d%E2%80%99afrique/

Christophe Cassiau-Haurie Histoire de la bande dessinée congolaise : Congo belge, Zaïre, République démocratique du Congo L'Harmattan 2010

Christophe Cassiau-Haurie L'histoire de la bande dessinée au Cameroun L'Harmattan, 2016

Dell, Simon, “Yeyap’s Resources: Representation and the Arts of the Bamum in Cameroon and France, 1902-1935) in World Art and the Legacies of Colonial Violence, ed. Daniel J. Rycroft. Routledge, 2016

Fine, Jonathan, “Selling Authenticity in the Bamum Kingdom, 1929-1930” in African Arts, Vol 49, No. 2, Summer 2016

https://www.academia.edu/25433151/Selling_Authenticity_in_the_Bamum_Kingdom_in_1929_1930

Fomine, Forka Leypey Mathew “A Concise Historical Survey of the Bamum Dynasty and the Influence of Islam in Foumban, Cameroon, 1390-Present” The African Anthropologist, Vol 16 Nos 1& 2, 2009

Forni, Silvia “Visual diplomacy: Art circulation and iconoclashes in the Kingdom of Bamum” in The Inbetweenness of Things: Materializing Mediation and Movement between Worlds, Paul Basu, ed. Bloomsbury, 2017

Galitzine-Loumpet, Alexandra, Reconsidering Patrimonialization in the Bamun Kingdom. African Arts Vol 49 No. 2, summer 2016

Galitzine- Loumpet, Alexandra, La cartographie du roi Njoya (Royaume Bamoun, ouest Cameroun) Représenter / traduire son espace-monde Le CFC (N°210- Décembre 2011)

Galitzine- Loumpet, Alexandra “Un art de “re action”: representation de soit et historiographie dans le royaume Bamoun,” paper presented at the XXIInd IAMHIST conference “Medias and Imperialism” University of Amsterdam (July 18-21, 2007). Unpublished

Galitzine-Loumpet, Alexandra, “Objets en exil; Les temporalités parallèles du trône du roi Bamoun Njoya (Ouest Cameroun) “ http://www.poexil.umontreal.ca/events/colloquetemp/actes/alexandra.pdf

Galitzine-Loumpet, Alexandra, “Ibrahim Njoya, maitre du dessin bamoun” Anthologie de l’Art en Afrique au XXème siècle, La Revue Noire Ed. December 2001 https://www.academia.edu/12010866/Ibrahim_Njoya_maitre_du_dessin_bamoun

Galitzine-Loumpet, Alexandra, Njoya et le royaume bamoun, KARTHALA Editions November 1, 2006

Geary, Christraud M., “Art Politics and the Transformation of Meaning: Bamum Art in the Twentieth Century” in African Material Culture Edited by Mary Jo Arnoldi, Christraud M Geary and Kris L Hardin , Indiana University Press, 1996 (CMG)

Geary, Christraud M. Visions of Africa: Bamum, 5 Continents Editions, Milan. 2011

Geary, Christraud M., Images from Bamum: German Colonial Photography at the Court of King Njoya, Smithsonian Institution Press 1988

Handelman, Susan. "God's Comics:The Hebrew Alphabet as Graphic Narrative" in Comics and Sacred Texts: Reimagining Religion and Graphic Narratives by Assaf Gamzou (Editor), Ken Koltun-Fromm (Editor) University Press of Mississippi (2018)

Hunt, Nancy Rose, “Tintin and the Interruptions of Belgian Comics,” in Images and Empires, ed. P. Landau and D. Kaspin University of California Press, 2002

Lent, John, ed. Cartooning in Africa, Hampton Press, 2009

Limb, Peter and Olaniyan, Tejumola , Taking African Cartoons Seriously: Politics, Satire and Culture, Michigan State University Press, 2018

Morin, Floriane, “The MEG Collection of the Precursors of African Pictorial Art,” in Leclair, Madeleine, Morin Floriane, Tamarozzi, Federica (eds). 2014. The Collections in Focus. Musée d'ethnographie de Genève. Exhibition catalogue. Genève: MEG / Morges: Glénat, 256 pages.

Morin, Floriane: https://www.academia.edu/30943334/The_MEG_Collection_of_the_Precursors_of_African_Pictorial_Art.pdf

Mount, Marshall Ward. African Art, The Years Since 1920. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, London. 1973

Nganang, Patrice, Mount Pleasant: a Novel Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016

Nganang, Patrice, “In Praise of the Alphabet” in Rethinking African Cultural Production, ed. Frieda Ekotto and Kenneth W. Harrow, Indiana University Press, 2015

Nganang, Patrice, “Writing Under Colonial Rule” in The Cultural Legacy of German Colonial Rule Ed. by Mühlhahn, Klaus. De Gruyter Oldenbourg 2017

Nicodemus, Everlyn, “African Modern Art and Black Cultural Trauma” Doctorate thesis, Middlesex University. School of Arts and Education January 2011

Ibrahim Njoya: 'The Mother Rat and her Children', translated by Nji Oumarou Nchare, Konrad Tuchscherer and Amy Reid, in: Pulsations: The Journal of New African Writing. The Red Sea Press, Trenton, New Jersey, 2012, pp. 127-139.

Orosz, Kenneth J., Njoya’s Alphabet: The Sultan of Bamum and French Colonial Reactions to the A ka u ku Script, Cahier d’études Africaines, No 217, 2015

Osayimwese, Itohan, Architecture and the Myth of Authenticity During the German Colonial Period, TDSR: Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review 24-2, Spring 2013

Sabran, Marguerite de, “La " Maison du pays ". L'exposition du patrimoine dans les musées privés d'Afrique de l'Ouest et du Cameroun” In: Cahiers d'études africaines, vol. 39, n°155-156, 1999. Prélever, exhiber. La mise en musées. pp. 885-903; doi : https://doi.org/10.3406/cea.1999.1783 https://www.persee.fr/doc/cea_0008-0055_1999_num_39_155_1783

Samuels, Natty Mark, Review of “Visual Arts in Cameroon,” www.readafricabooks, posted February 7, 2018

Claude Savary « Situation et histoire des Bamum » Bulletins annuels du Musée d’Ethnographie de la Ville de Genève, Nos 20, 1977, 21-22, 1978-1979

Schemmel, Annette, “Visual Arts in Cameroon, a Genealogy of Non-formal Training, 1976-2014” Langaa Research & Publishing CIG. Bamenda, Cameroon. 2015

Tardits, Claude, L’histoire singulière de l’art bamoun Maisonneuve & Larose, Paris, 2004

Tardits, Claude., Le Royaume Bamoum, A. Colin, Paris 1980

Tardits, Claude “Pursue to Attain: a Royal Religion” in African Crossroads: Intersections between History and Anthropology in Cameroon. Ed: Ian Fowler, David Zeitlyn, Bergahn Books, 1996

Various Les dessins Bamum, Musée d’Arts Africaine, Océaniens, Amérindiens, Marseilles, 1997. Sections:

Tardits, Claude, “Un grand dessinateur: Ibrahim Njoya”

Njoya, Idrissou, “Le dessin d’art Bamum” 45-52

Nicolas, Alain & Sourrieu, Marianne, “Presentation”: 15-20

END NOTES:

- (for a concise overview on contemporary African comics, see http://professorlatinx.com/comics/sub-saharan-african-francophone-comics/See also Limb, Peter and Olaniyan, Tejumola , Taking African Cartoons Seriously: Politics, Satire and Culture, Michigan State University Press, 2018

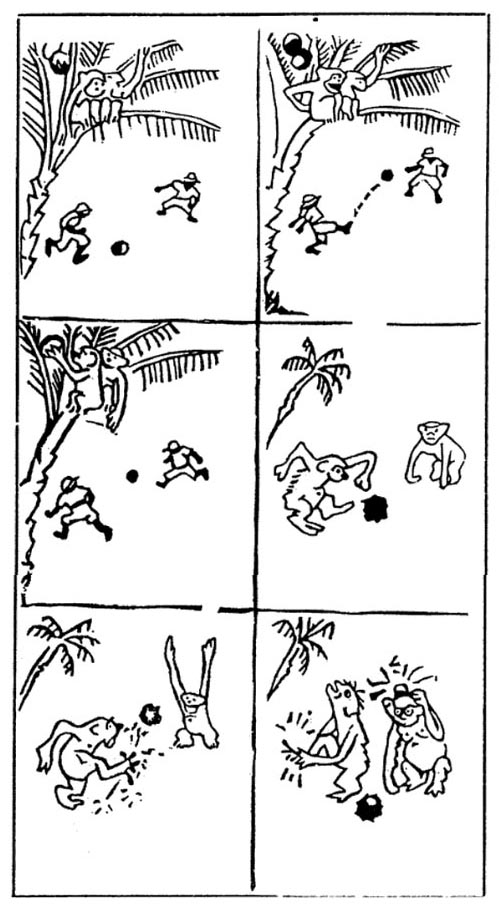

- The first known comic drawn by an African, this one-shot script has been interpreted as a racist metaphor in which the monkeys who imitate soccer players representing Africans trying to become like Europeans

- See Lent, John, ed. Cartooning in Africa, Hampton Press, 2009; Nancy Rose Hunt, “Tintin and the Interruptions of Belgian Comics,” in Images and Empires, ed. P. Landau and D. Kaspin University of California Press, 2002; Christophe Cassiau-Haurie Histoire de la BD Congolaise L'Harmattan 2010

- Galitzine-Loumpet, Alexandra, Njoya et le royaume bamoun, KARTHALA Editions November 1, 2006

- http://bdzoom.com/64560/patrimoine/hommage-a-ibrahim-njoya-premier-auteur-de-bande-dessinee-d%E2%80%99afrique/

- Nicodemus, Everlyn, “African Modern Art and Black Cultural Trauma” Doctorate thesis, Middlesex University. School of Arts and Education January 2011

- Geary, Christraud M. “Visions of Africa: Bamum” 5 Continents Editions, Milan. 2011, p. 21

- Osayimwese, Itohan, Architecture and the Myth of Authenticity During the German Colonial Period, in TDSR: Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review 24-2, Spring 2013, p 12. See also Geary, Christraud M. Visions of Africa: Bamum 5 Continents Editions, Milan. 2011, p. 18

- Orosz, Kenneth J., Njoya’s Alphabet: The Sultan of Bamum and French Colonial Reactions to the A ka u kuScript, Cahier d’études Africaines, No 217, 2015

- "Nji" is an honorific title for the head of a noble family lineage

- Geary, Christraud M. Visions of Africa: Bamum, 5 Continents Editions, Milan. 2011.

- Njoya, Rabiatou, Les dessins Bamum, Musée d’Arts Africaine, Océaniens, Amérindiens, Marseilles, 1997 p. 42, Orosz, Kenneth J., Njoya’s Alphabet: The Sultan of Bamum and French Colonial Reactions to the A ka u ku Script, Cahier d’études Africaines, No 217, 2015

- The number usually cited for the first version of Bamum script is 510, see Njoya, Rabiatou, Les dessins Bamum. Kenneth J. Orosz puts the number at over 1000. See page 6, Orosz, Kenneth J., Njoya’s Alphabet: The Sultan of Bamum and French Colonial Reactions to the A ka u ku Script, Cahier d’études Africaines, No 217, 2015.

- Nganang, Patrice, “In Praise of the Alphabet” in Rethinking African Cultural Production, ed. Frieda Ekotto and Kenneth W. Harrow, Indiana University Press, 2015

- Tardits, Claude, “Un grand dessinateur: Ibrahim Njoya” Les dessins Bamum, Musée d’Arts Africaine, Océaniens, Amérindiens, Marseilles, 1997

- Galitzine-Loumpet, Alexandra, Njoya et le royaume bamoun, KARTHALA Editions November 1, 2006 p. 48, Geary, Christraud M. Visions of Africa: Bamum, 5 Continents Editions, Milan. 2011 p24

- Tardits C., Le Royaume Bamoum, A. Colin, Paris 1980p347

- Geary, Christraud M. Visions of Africa: Bamum, 5 Continents Editions, Milan. 2011 p23; Tardits C., Le Royaume Bamoum, A. Colin, Paris 1980p347 p356)

- Geary, Christraud M. Visions of Africa: Bamum, 5 Continents Editions, Milan. 2011 p. 48. Mount, Marshall Ward. African Art, The Years Since 1920. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, London. 1973 p 163

- In Le Royaume Bamum, (ms. p 51) Historian of the Bamum kingdom Claude Tardits says that there were two versions of Nwet Kwete commissioned by Sultan Njoya, in different versions of the Bamum writing system, one in 1916, another, incomplete, in 1922. I’m not sure which version these pages, and the ones below, are from. They are reproduced, undated, in Le Dessins Bamum.

- Tardits, Claude “Pursue to Attain: a Royal Religion” in African Crossroads: Intersections between History and Anthropology in Cameroon. Ed: Ian Fowler, David Zeitlyn, Bergahn Books, 1996

- Nicolas, Alain & Sourrieu, Marianne, “Presentation”: 15-20, in Les dessins Bamum, Musée d’Arts Africaine, Océaniens, Amérindiens, Marseilles, 1997 p18

- Njoya, Idrissou, “Le dessin d’art Bamum” in Les dessins Bamum, Musée d’Arts Africaine, Océaniens, Amérindiens, Marseilles, 1997. Tardits C., Le Royaume Bamoum, A. Colin, Paris 1980 ms. p210. Orosz, Kenneth J., Njoya’s Alphabet: The Sultan of Bamum and French Colonial Reactions to the A ka u ku Script, Cahier d’études Africaines, No 217, 2015 p 10. Galitzine-Loumpet, Alexandra, “Ibrahim Njoya, maitre du dessin bamoun” Anthologie de l’Art en Afrique au XXème siècle, La Revue Noire Ed. December 2001

- Njoya, Idrissou, “Le dessin d’art Bamum” in Les dessins Bamum, Musée d’Arts Africaine, Océaniens, Amérindiens, Marseilles, 1997 p46

- Mount, Marshall Ward. African Art, The Years Since 1920. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, London. 1973

- Geary, Christraud M. Visions of Africa: Bamum, 5 Continents Editions, Milan. 2011

- Galitzine- Loumpet, Alexandra, La cartographie du roi Njoya (Royaume Bamoun, ouest Cameroun) Représenter / traduire son espace-monde Le CFC (N°210- Décembre 2011

- Dell, Simon, “Yeyap’s Resources: Representation and the Arts of the Bamum in Cameroon and France, 1902-1935) in World Art and the Legacies of Colonial Violence, ed. Daniel J. Rycroft

- Galitzine-Loumpet, Alexandra, Njoya et le royaume bamoun, KARTHALA Editions November 1, 2006 p. 72

- Tardits, Claude., Le Royaume Bamoum, A. Colin, Paris 1980 p. 933 The report written in Douala by the colonial Battalion Chief Martin on Dec 27 1919.

- Simon Dell dates the opening of Yeyap's museum to 1920 in “Yeyap’s Resources: Representation and the Arts of the Bamum in Cameroon and France, 1902-1935" on the other hand, Alexandra Galitzine-Loumpet asserts in "Reconsidering Patrimonialization in the Bamum Kingdom" that there is no contemporary record of a formal museum opening before 1929.

- Morin, Floriane, “The MEG Collection of the Precursors of African Pictorial Art,” in Leclair, Madeleine, Morin Floriane, Tamarozzi, Federica (eds). 2014. The Collections in Focus. Musée d'ethnographie de Genève. Exhibition catalogue. Genève: MEG / Morges: Glénat, 256 pages

- Claude Savary « Situation et histoire des Bamum » Bulletins annuels du Musée d’Ethnographie de la Ville de Genève, Nos 20, 1977, 21-22, 1978-1979

- Geary, Christraud M., “Art Politics and the Transformation of Meaning: Bamum Art in the Twentieth Century” in African Material Culture Edited by Mary Jo Arnoldi, Christraud M Geary and Kris L Hardin , Indiana University Press, 1996

- Dell, Simon, “Yeyap’s Resources: Representation and the Arts of the Bamum in Cameroon and France, 1902-1935) in World Art and the Legacies of Colonial Violence, ed. Daniel J. Rycroft. Routledge, 2016

- Fine, Jonathan, “Selling Authenticity in the Bamum Kingdom, 1929-1930” in African Arts, Vol 49, No. 2, Summer 2016

- Dell, Simon, “Yeyap’s Resources: Representation and the Arts of the Bamum in Cameroon and France, 1902-1935) in World Art and the Legacies of Colonial Violence, ed. Daniel J. Rycroft. Routledge, 2016

- Galitzine-Loumpet, Alexandra, Reconsidering Patrimonialization in the Bamun Kingdom. African Arts Vol 49 No. 2, summer 2016 p 73

- Nganang, Patrice, “Writing Under Colonial Rule” in The Cultural Legacy of German Colonial Rule Ed. by Mühlhahn, Klaus. De Gruyter Oldenbourg 2017

- Geary, Christraud M. Visions of Africa: Bamum, 5 Continents Editions, Milan. 2011

- Orosz, Kenneth J., Njoya’s Alphabet: The Sultan of Bamum and French Colonial Reactions to the A ka u ku Script, Cahier d’études Africaines, No 217, 2015

- Claude Savary « Situation et histoire des Bamum » Bulletins annuels du Musée d’Ethnographie de la Ville de Genève, Nos 20, 1977, 21-22, 1978-1979

- Tardits, Claude, “Un grand dessinateur: Ibrahim Njoya” in Les dessins Bamum, Musée d’Arts Africaine, Océaniens, Amérindiens, Marseilles, 1997

- quoted in Nganang, Patrice, “Writing Under Colonial Rule” in The Cultural Legacy of German Colonial Rule Ed. by Mühlhahn, Klaus. De Gruyter Oldenbourg 2017, p 74 .

- Dell, Simon, “Yeyap’s Resources: Representation and the Arts of the Bamum in Cameroon and France, 1902-1935) in World Art and the Legacies of Colonial Violence, ed. Daniel J. Rycroft. Routledge, 2016 p.51

- "a figurehead whose moral authority could be harnessed in support of government decisions," Orosz, Kenneth J., Njoya’s Alphabet: The Sultan of Bamum and French Colonial Reactions to the A ka u ku Script, Cahier d’études Africaines, No 217, 2015

- Samuels, Natty Mark, Review of “Visual Arts in Cameroon,” www.readafricabooks, posted February 7, 2018

- Schemmel, Annette, “Visual Arts in Cameroon, a Genealogy of Non-formal Training, 1976-2014” Langaa Research & Publishing CIG. Bamenda, Cameroon. 2015

- Nganang, Patrice, “In Praise of the Alphabet” in Rethinking African Cultural Production, ed. Frieda Ekotto and Kenneth W. Harrow, Indiana University Press, 2015

- Nicolas, Alain & Sourrieu, Marianne, “Presentation”: 15-20, in Les dessins Bamum, Musée d’Arts Africaine, Océaniens, Amérindiens, Marseilles, 1997 p17)

- Galitzine-Loumpet, Alexandra, “Ibrahim Njoya, maitre du dessin bamoun” Anthologie de l’Art en Afrique au XXème siècle, La Revue Noire Ed. December 2001

- Schemmel, Annette, “Visual Arts in Cameroon, a Genealogy of Non-formal Training, 1976-2014” Langaa Research & Publishing CIG. Bamenda, Cameroon. 2015 p.53

- translated in[Claude Savary « Situation et histoire des Bamum » Bulletins annuels du Musée d’Ethnographie de la Ville de Genève, Nos 20, 1977, 21-22, 1978-1979

- Schemmel, Annette, “Visual Arts in Cameroon, a Genealogy of Non-formal Training, 1976-2014” Langaa Research & Publishing CIG. Bamenda, Cameroon. 2015 p 57-59

- Claude Savary « Situation et histoire des Bamum » Bulletins annuels du Musée d’Ethnographie de la Ville de Genève, Nos 20, 1977, 21-22, 1978-1979

- Claude Savary, "Situation et histoire des Bamun" in the Bulletin Annuel du Musée d’Ethnographie - Genève, No 21-22, 1978-1979

- Claude Savary, "Situation et histoire des Bamun" in the Bulletin Annuel du Musée d’Ethnographie - Genève, No 21-22, 1978-1979

- Claude Savary, "Situation et histoire des Bamun" in the Bulletin Annuel du Musée d’Ethnographie - Genève, No 21-22, 1978-1979

- Tardits, Claude., Le Royaume Bamoum, A. Colin, Paris 1980, p 86 The notion of Syrian/Egyptian origins of Bamum people were attributed by Tardit to the Bamum Academy established in 1944, suggesting a date not prior to that for Njoya’s comic.

- Tardits, Claude, L’histoire singulière de l’art bamoun Maisonneuve & Larose, Paris, 2004 p.105-106

- Tardits, Claude, L’histoire singulière de l’art bamoun Maisonneuve & Larose, Paris, 2004 p118

- Galitzine-Loumpet, Alexandra, Njoya et le royaume bamoun, KARTHALA Editions November 1, 2006 p 193-194

- Tardits, Claude., Le Royaume Bamoum, A. Colin, Paris 1980 p. 347 and see bibliography, 1027-1028. Also see Galitzine-Loumpet, Njoya et le royaume bamoun, p 129 for more historical writings by Ibrahim

- Alexandra Galitzine-Loumpet dates Njoya's death as August 9, 1966 (Galitzine-Loumpet, Alexandra, “Ibrahim Njoya, maitre du dessin bamoun” Anthologie de l’Art en Afrique au XXème siècle, La Revue Noire Ed. December 2001), as does Geary in Visions of Africa: Bamum. I'm persuaded by Annette Schemmel's case for the earlier date in “Visual Arts in Cameroon, a Genealogy of Non-formal Training, 1976-2014” (footnote 27 p321)

- https://eap.bl.uk/archive-file/EAP051-1-1-12-530 Another letter with Islamic theme: https://eap.bl.uk/archive-file/EAP051-1-1-12-373

- Nganang, Patrice, Mount Pleasant: a Novel., Farrar, Straus and Giroux (April 12, 2016) , translator Amy Baram Reid, p. 188