Iasmin Omar Ata’s debut graphic novel Mis(h)adra, adapted from their webcomic of the same name, follows a young man named Isaac through suffering from epilepsy, dealing with difficult and stigmatizing doctors, and making his way through college. Drawn with bright, poppy colors in a style influenced by Osamu Tezuka and other manga, Ata visualizes epileptic attacks looming as daggers with eyes, unseen to the world around Isaac but all too prominent for him. I spoke to Iasmin over Skype.—Annie Mok

Iasmin Omar Ata’s debut graphic novel Mis(h)adra, adapted from their webcomic of the same name, follows a young man named Isaac through suffering from epilepsy, dealing with difficult and stigmatizing doctors, and making his way through college. Drawn with bright, poppy colors in a style influenced by Osamu Tezuka and other manga, Ata visualizes epileptic attacks looming as daggers with eyes, unseen to the world around Isaac but all too prominent for him. I spoke to Iasmin over Skype.—Annie Mok

ANNIE MOK: Let’s start with the title Mis(h)adra. Is that how it’s pronounced, with a rolling “r”?

IASMIN OMAR ATA: Pretty much. It’s kind of awkward for non-Arabic speakers to say. I say “mish-ah-dra.” However people can pronounce it is fine by me, because I know it is a little bit awkward. Mishadra in the dialect of Arabic that me and my family speak means “I can’t” or “cannot.”

MOK: What’s that dialect?

ATA: Like, Palestinian, Lebanese Arabic, more of a colloquial… Misadra means “seizure” or “captivation.” Like a triple, cross-language pun [laughs].

MOK: So the story follows Isaac, this young man who’s in college, and you said the story is semi-autobiographical? How would you categorize it as, what’s its relation to your life story?

ATA: It’s very similar. Pretty much everything that’s happened in the book, with some exceptions and rearranging has happened to me. This is all sort of a re-versioning and in my own way a processing of these events that have happened to me. Some details are changed, and some characters represent people but aren’t real people in my life, represent concepts and things I’ve interacted with. It’s just in the avatar as Isaac.

MOK: What was it like to go with Isaac and to kind of repurpose your life into this other purpose.

ATA: I’m not actually very good at talking about myself directly, so it was really hard for me to try and figure out a way to process all this stuff through art. I felt that to have it go through a character who isn’t quite me, is very similar, in that way I was able to distance myself. Get a perspective on events that I was writing, not be 100% in my own head to have a character that was representative of me. Look at things in a new light. That was helpful to recontextualize things I was going through, but also help me get comfortable writing about things that happened to me. Because it wasn’t just my face looking right at the reader, it gave me a safer or more comfortable place.

MOK: In what ways is Isaac different from you?

MOK: In what ways is Isaac different from you?

ATA: Isaac is more me in the past. He started in a place that I was a few years ago, when I really had no idea how to handle my illness. I was just diagnosed awhile before I started [the comic] and I didn’t know how to handle things. He’s different from me in the way that he is more in the past, dealing with things in a different way. At the same time, as I started making the comic, I started to process my illness differently, I started to become more functional, because it was basically art therapy. Isaac at the end of the comic, where he’s like, I accept this and I’m kind of moving on and can deal with my illness, that was where I was at the end of the comic. So in a strange way, he started off different from me, but we grew very similar.

MOK: I wanted to talk about color. The version I have is the advance preview edition in which only the intro is in color, but you use these stark contrasts of very dark pages filled with black ink, or digital ink, I’m not sure how you’re working on these pages?

ATA: Digital. They started off, I pencil manually on pages and then I scan them and do the inks.

MOK: Can you talk about building this contrast between this frightening world of epilepsy attacks that Isaac is getting, and also his day-to-day world where the attacks are looming. What was it like to build these dichotomies of visual languages?

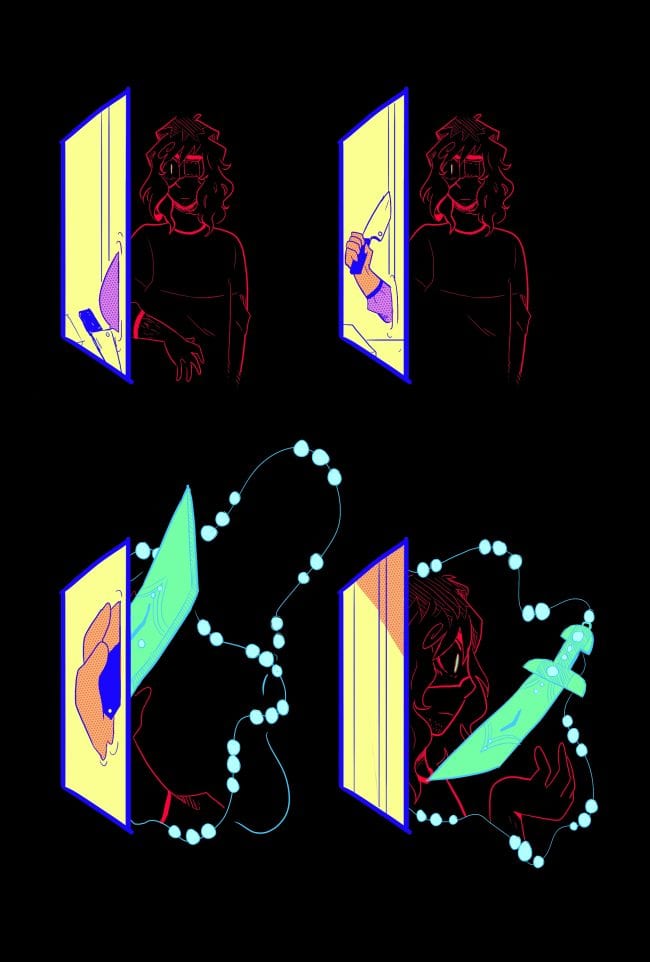

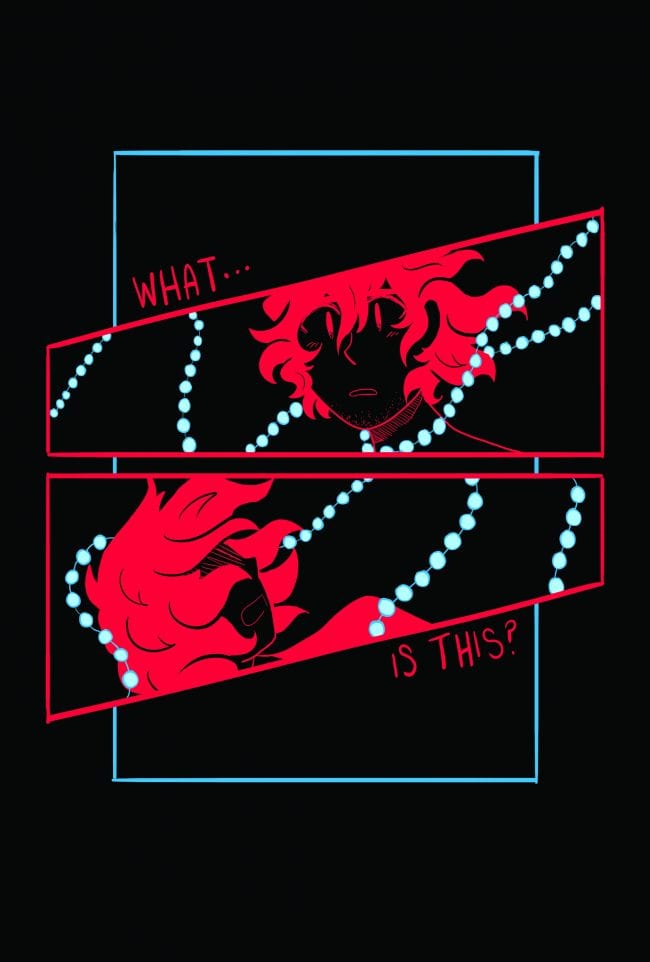

ATA: From the very beginning, it was sort of a long process trying to figure out what the hell the comic was going to look like. I was trying to create a more visceral feeling when you’re looking at Isaac’s life and what he encounters. Rather than being like, “I’m scared” or “I’m very anxious about this,” I wanted it to come across in the fabric of the comic itself without Isaac telling you straight up. That helps people suture into the narrative a bit more. I did a lot of work in the beginning, figuring out, and for me the contrast is important. It looks pretty ordinary, day-to-day, but you have the visualization of the danger of seizures as these brightly-colored daggers. They’re conspicuous, almost in the way. When it comes having a seizure, I wanted the colors to not necessarily be inverted but kind of different. When a seizure’s happening to me, it feels almost like I’m being transported into a different world. There is a huge contrast between your day-to-day and the moment where it’s coming, it’s happening.

MOK: You serialized [online].

ATA: I was basically doing a chapter every month. There were a few small hiatuses, but I put the first chapter online in November 2013, and it ran as a webcomic til fall 2015. I never printed it because as much as I wanted to, it was such a massive project and I could never afford it [laughs]. Then right after the comic finished out at the end of 2015 I started working with my current agent who’s amazing. She started looking around, we started figuring what would be the best option, as far as publishing goes. We found Gallery 13, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, at the end of last year. Overall it’s been about four years.

MOK: And the webcomic finished before you were looking for a publisher.

ATA: Yes, though I did have to completely figure out the colors, not from scratch, but I had to do a lot of work making the comic from RGB web format color to CMYK. There are a couple of cleanups, there are a couple of things changed to make it more readable. When I first started the comic, the lettering was terrible [laughs], so bad. It’s very, very similar to the original version.

MOK: I love this half-tone dot pattern. It calls back to me classic comics and zines and manga. Was there an influence for that?

ATA: I’m not sure if there’s a specific place I was drawing it from. I am obviously very manga-influenced and had wanted to work with screentones for awhile. At the time I thought instead of just a solid color, the halftone kinda helped it pop.

MOK: “Pop” is the right word. What was it like working with Gallery 13? Are they a new imprint?

ATA: They’re pretty new, I think. So far, and I think in the future, it’s really been amazing. They’ve been very nice, very pleasant. A lot of good energy surrounding the work. And it is interesting to be a genderqueer author who is going into “triple-A” publishing or whatever the term is, and I think when you go in, there’s an anxiety of… You know, I have to explain this, and hopefully people are okay and respectful. I had that conversation with Gallery 13, just being this is what it is, and they’ve been so amazing about it.

MOK: With the themes of dichotomy of the book, near the end, Isaac confronts his double. Did this ring with the dichotomy you were trying to make between seizure world, and like, regular world?

ATA: There definitely is a divide there. You’ll notice his double has the missing eye, but it’s not quite there, it’s sort of fantastical. It’s in the same style as the daggers. There’s a divide there between the functional part of Isaac, and the other part that’s the very real depression. That’s like, “I don’t wanna fix it, I just wanna lay down!” [laughs]. There’s that part where I’m really trying to function properly in this society, and then inside there’s this frustration that I can’t really compartmentalize in my day-to-day.

MOK: I wanted to ask about the daggers, because you have this clear symbology of the daggers with eyes, representing seizures oncoming. How did you develop that?

MOK: I wanted to ask about the daggers, because you have this clear symbology of the daggers with eyes, representing seizures oncoming. How did you develop that?

ATA: I wanted to put iconography of the seizures, again, going into the suture of the narrative, don’t just tell people, show don’t tell. And I thought that was important for a comic about illness, especially one that is very misunderstood. Even if you don’t 100% get everything about epilepsy, or you don’t relate, the idea that there is something dangerous following you, watching you and thus the eyes, is more relatable across the board. It helps people get into it and feel what Isaac’s feeling. I chose a dagger with eyes so you’re just constantly being followed and being watched, ‘cause that’s what it feels like. With epilepsy, everyone has a different experience, but with mine and I think with a lot of other peoples’, there’s the feeling that it never really goes away. Even on days when you’re feeling kind of alright, and you’re feeling mostly functional, you’re never at 0%. It’s always watching you, it’s always there to some extent. That’s the origin of that iconography. I chose that specific dagger, which people in English refer to as the Arabic dagger, also referred to as the jambiya, which is a particular type of dagger in classic Arab culture, particularly in the Gulf that is often worn. A lot of times, it can represent protection in a way, but I did want to subvert that with this weapon that is tied to my culture but present in a way where I think you can understand it even if you don’t know where it comes from.

MOK: Talking about images specific to comics reminds me of your work in games. I wanted to ask about your work in games, what your relationship to it is like. You worked on this game Four Horsemen, a visual novel, in which four teens are the horsemen of the apocalypse. Can you talk about your relationship with games?

ATA: I always loved games, since I was a kid, and it was always kind of a far-off thing, like maybe I would make my own someday… Recently a lot of my favorites have been creator-made RPG Maker games, because there’s something so great about where they come from, and having a very small group of people or one person working on this project with an accessible software. I started to realize, there’s more accessibility, there’s more software out there that allows people to make games and have a shot at it without having to get involved in this big and admittedly very flawed industry. In 2015, I met Kevin Chen, the director of Four Horsemen. Around the same time, I started working on another visual novel called Ghosts of Miami. It was switching on and off doing characters [for Four Horsemen] and backgrounds [for Ghosts of Miami], in the same day sometimes [laughs]. My relation to games is so funny, it just happened so quickly. And I was working on a third game, I did a really short abstract adventure game called Being in RPG Maker for a gallery show about Palestinian solidarity and lived experience. About a half-hour long, and it’s supposed to convey, similarly to Mis(h)adra, where I tried to use iconography and ways to immerse the audience into something they may not understand or have experienced. Three games in a year and a half or something like that [laughs].

MOK: Are you aware of Soha Kareem’s work? ...She’s a games maker and critic, and has made at least one game [Penalties] about Palestinian experiences.

ATA: I will have to check that out!

MOK: My favorite of hers is a game [reProgram] about kink, and using kink to work through depression and trauma.

ATA: I would love to see that because that sounds great [laughs]. It just makes me really hype to see middle eastern voices and Arab voices in games and any media really, but particularly Palestinian voices. It’s a very ignored voice, even though we have gone through so much [sadly laughs], and there’s so much to say… Games and comics are my two favorite things to work in, and as Mis(h)adra is wrapping up, I have five games I wanna make and I gotta pick one!

MOK: Can you tell me about what you might make?

ATA: I have been throwing around the idea—this wouldn’t be til mid-next year, probably—I have been thinking of a game processing some trauma that I’ve been through. In a similar way, where it is part of the narrative, but there’s a lot of different things that help you work into it. I’ve been thinking about making this sort of adventure game in RPG Maker about processing trauma, and my goal is to try to get it out around Mother’s Day next year. You can probably connect the dots there [laughs].

MOK: I’m your girl [laughs]! I will play this game and cry endlessly.

ATA: Thank you [laughs]! I don’t wanna say too much about it ‘cause you know, Inshallah. The point is I have a lot of games ideas right now and that I know it’s possible.

MOK: I’m really appreciative that you’re talking about trauma. In the book, you get to this character who’s talking about her depression, and how she also gets attacks, anxiety attacks… I found a lot to empathize with, with the idea of triggers being everywhere, and never being able to shut off. That resonated with me very deeply.

ATA: I’m very happy to hear that, ‘cause obviously I want epileptics to read it, but I also am happy that anybody who has something that they’re dealing with internally looks to me and is like, “I can relate to this even though I don’t have epilepsy.” I think a lot comes from the fact that epilepsy is sort of a package. It’s an all-encompassing package where almost by default you get anxiety and depression and PTSD and all this stuff just because of the nature of the illness. It comes often, not for everybody, but it is common. Just the general idea, of something constantly being on your mind, or being a threat to you that people can’t see. You have to have this point where it’s like, what am I going to do about this? So I’m glad that comes across to non-epileptics as well.

MOK: That point you describe of “What am I going to do about this,” that seems like the conclusion of the book. That point where Isaac says something like, “I want to live, I need to live.” That seems so much like the point that you reached maybe as a person as well as a creator.

ATA: It’s interesting, that point was around the time I started making the comic. Like, I need to live with this, and for lack of a better phrase, deal with this in some way, to get into a healthy place. That’s part of why I started making the comic in the first place. Because of Mis(h)adra.... if I hadn’t made the comic, I wouldn’t be nearly as functional as I am now. It really was a point of art therapy. That point is similarly where Isaac leaves off. Now he’s at a point where he can really work towards being in a healthy place. And it’s up to the reader, I guess [laughs]... Things wrap up in a hopeful place, and even if he says things aren’t gonna be easy and it won’t happen overnight, but I’m at least mentally in a place where I can work towards being happy and healthy and functional, all things considered.