We are at peak reprint. Because of this, the only worthwhile publishing projects reissuing old comic strips or books need to be either uncovering hidden gems and critical missing links to bygone eras, or repackaging material in a way that makes it more historically relevant or capital-I “Important.” Craig Yoe does neither.

The hardcovers discharged monthly by the IDW imprint Yoe Books have varying themes and subject matters, ranging from wacky horror stories and wacky romance stories, all the way to wacky funny-animal stories. Yoe Books look like they’ve been put through the Print Shop Deluxe ringer. They are all faux-sturdy, piss-poor print jobs, and committed to a cookie-cutter 9”x11” template, no matter the size or layout of the original material. This is because Yoe is the Spencer’s Gifts of archivists—forever more interested in novelty than preservation.

Eyes that go googly over nostalgia are often clouded by it as well. That can be the only reason these books look like they are assembled from color Xerox copies. It appears that the pages were scanned from the original comic book, blown up, and then that enlargement was shrunk down again to fit the book’s page size. That is why you have panels that look this, by Jack Cole, Dan DeCarlo, and Carl Barks, respectively shown no respect:

If luxury coffee-table books are just as disposable as the original dime-store floppies, then what’s the point? I’m sure there’s an artistic and aesthetic argument about whether or not to alter or recolor the original pages, but I truly don’t think Yoe and his team are engaging in that discussion. They’re just lazy and thoughtless.

A few years back, I was excited to pick up the collected Comic Book by John Kricfalusi and the other Spumco animators. Minutes after opening the front cover, I had questions: Why are some stories in black and white and others in color? Why are only two out of the four issues gathered? Why is there a solitary drawing of Björk on the back cover? The introduction would surely explain all of this, but there wasn’t one. It just opens right onto the first page of the comic. Shame on me for not doing my due diligence. This was a Yoe Book, after all. Why would questions be answered? Throw your inquiries and sound publishing practices to the wind, put on a fez, and join the “Yippie Yi Yoe Society!” Satisfactory reading experiences are for squares, man.

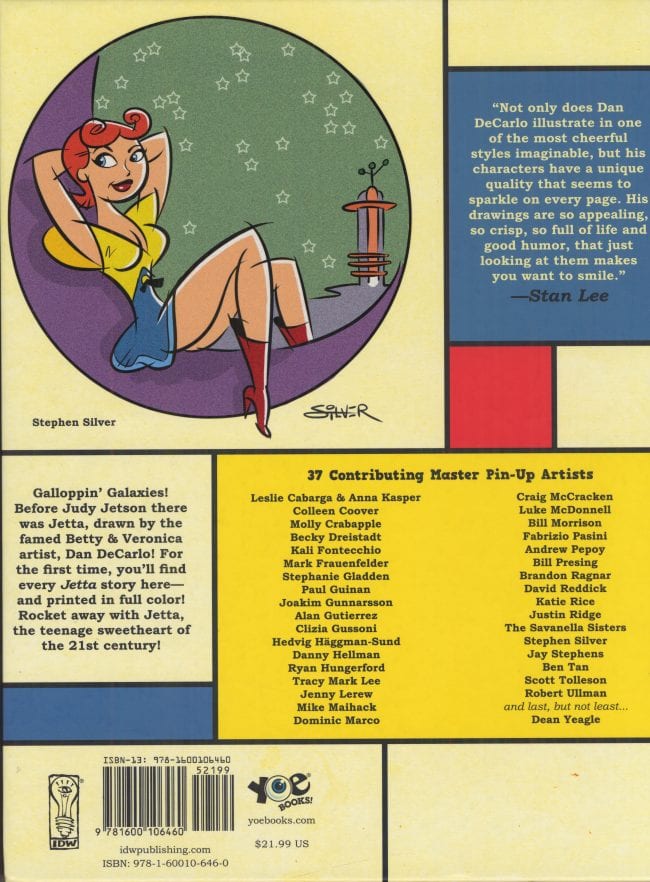

You’ll notice that the narrow borders of Yoe’s limited taste and aptitude for design are mirrored by the borders he utilizes on the front covers of nearly all his books. The back covers are not much better.

I too have always felt like the only thing Piet Mondrian was missing was a whole shitload of text. Below, you’ll see the back cover of a collection of Billy DeBeck’s Barney Google.

If you thought this was minimal, wait until you see the spine, which doesn’t feature the name of the book or the artist. (But sure does include the Yoe Books logo!)

All of these choices are unintentionally comical, sure, but they point to something deeper and depressing. With all these goofy, throwaway intentions comes contempt for the creators. Comics are art—that battle has been fought and won—but Yoe fumbles with this idea as much as he does with a high-res scanner. He has published books (albeit lesser works) by the upper echelon of cartoonists. People like Dick Briefer, Steve Ditko, and Frank Frazetta deserve the appreciation they’ve rightly garnered, but when published by Yoe Books, they are always second on the call sheet. That’s because Craig Yoe values the collector over the artist. For him, the wistful idea of a rolled-up comic book stuffed into the pocket of his dungarees trumps the tangible fact that these cartoonists unceremoniously toiled away years of their lives to create all this “dumb fun.”

But don’t get me wrong, these books aren’t all bad. You can still learn valuable history lessons from reading through the Yoe Books library. Each one is an education into how tangentially-related, middling talents happy to casually speak for artists while also taking them for granted have been around since the comics business began. They are frank reminders that hoarder-fanboys-cum-editors can continue to con publishers into putting their names in bold on the front covers of other people’s work. They are master classes in failing upward long enough that you might be rewarded with your very own imprint.

Is comics history worse off because these books are haphazardly published? The answer is a definitive yes. Print it front and center, in letters larger than the artists’ names.