Our Pilgrim forefathers and foremothers were fond of moral codes. Prominent among the many they embraced was a dress code that, based on social status and, of course, gender, governed what they could wear.

Our ancestors were one in a long line of societies in which religion’s defining struggle—the war against the flesh—revealed itself in ideas about clothing. These codes have been most visible in female fashion: since the sight of an ankle or a wrist can instantly send men into a sexual frenzy, they must be protected, not from female temptresses, but from themselves, from their own uncontrollable animalistic and even monstrous nature.

The actions of fanatical males around the world remind us that a woman can be stoned (or worse) if she fails to comply with her culture’s dress code. It would be easy, then, to think that such codes are fundamentally about the patriarchy’s need to control girls and women, while liberating boys and men. But such systems also tell us about males’ fears and desires about other males’ bodies.

***

Like the Pilgrims, another moral community with strict ideas about clothing is one we could call the DC-MarvelVerse (DCMV), the world of contemporary mainstream superhero comics. When critics write about DCMV superhero uniforms, they typically focus on the significance of what such outfits expose, while overlooking the meanings of what they conceal—often the entire male body.

In a strange way, male superhero costumes function like Puritan garb or even the Burka, an outfit that suppresses a secret (sexual) identity.

In arguments about superhero sexism, writers assume that veiled male bodies demonstrate unquestionable respect for the male form. These arguments adhere to a basic model of "harm/benefit analysis": if regulations hurt one gender, then the other must profit. While superhero comics are undeniably grounded in the objectification of women, I think we should explore the meanings of these codes for men as well. Maybe Batman’s ‘Bat-Burka’ should prompt us to wonder why male heroes must be covered.

One explanation for the male cover-up—as for all cover-ups—is that there's something to hide. Just as the mandatory Burka expresses fears about female bodies and male desire, the superhero costume reflects similar sexual anxieties. We often think of the mainstream superhero comic as a “power fantasy” without acknowledging its sexual dimension: it’s an erotic power fantasy. Perhaps some readers would be willing to admit that heroic tales are fantasies: “I would like to have the super power a superman has.” They might be less inclined to admit that these stories are heterosexual male domination fantasies: “I would like to have the power to control hot females” (yet to admit this would be to acknowledge that these comics’ chivalric code is a sham). Most readers would find it far too scary to recognize that these comics may be homoerotic fantasies: “Watching male bodies in close contact in the male-centric DCMV turns me on.” The hidden body is an unconscious emblem of forbidden same-sex desire.

In recent online essays, writers like Kelly Thompson and others argue that superhero comics celebrate the male body by representing heroes as idealized athletes. Yet, for me, DCMV heroes are inherently un-athletic. Actual male athletes are built for strength, speed, agility, and endurance—think of bodies like those of Lance Armstrong, Hector “Macho” Camacho, or LeBron James. Even some of the strongest male athletes, such as NFL linebackers, lack super-bodies. In real-world situations, superheroes’ malformed, grotesque, and clumsy bodies would inhibit effective superheroing. Like the bodybuilder forms they exaggerate, they are built, not for action, but for posing; they display a physically self-destructive narcissism. Along with female superheroes, Epic Male Superheroes are poseurs first, crime fighters second, and athletes never:

When we watch male athletes at work (in basketball, track and field, wrestling), we see lots of exposed flesh. So why not in superhero comics? We might say, “Well, the heroes are fighting and want to protect their bodies.” (Yet even many WWE wresters show a lot more flesh). But this argument—this recourse to realism—doesn’t explain why something is the way it is in a fantasy. We could ask why heroes don’t wear lightweight super-protective armor designed by Iron Man’s Stark Industries, or why they don’t just treat their skin with a magic formula (created by Mr. Fantastic) that protects it from super-villain laser bolts. Or why not go naked as a sign of unrestrained liberated power, like Moore and Gibbons’s Dr. Manhattan? But such questions ignore what these fantasy comics are about.

It might be that, when male bodies are completely covered, it's safer for male readers to identify with superheroes. Their muscles are not those of a good-looking real man, but rather a metaphorical index of a hero’s violent power, which, of course, is to be used only for good . . .

If the hyperactive musculature were exposed, these male forms would be revealed for what they really are: super grotesque. (I have never known a single person, male or female, who thought bodybuilders sexually attractive.) The hero costumes ensure that the covered super-body works symbolically: an over-muscled body signals raw power, not raw sexiness. The cover up has more to do with male fear than male privilege. Where have the visible firm young thighs of impressionable sidekicks like Robin gone? [See here for images of Robin's costume over time.]

If the hyperactive musculature were exposed, these male forms would be revealed for what they really are: super grotesque. (I have never known a single person, male or female, who thought bodybuilders sexually attractive.) The hero costumes ensure that the covered super-body works symbolically: an over-muscled body signals raw power, not raw sexiness. The cover up has more to do with male fear than male privilege. Where have the visible firm young thighs of impressionable sidekicks like Robin gone? [See here for images of Robin's costume over time.]

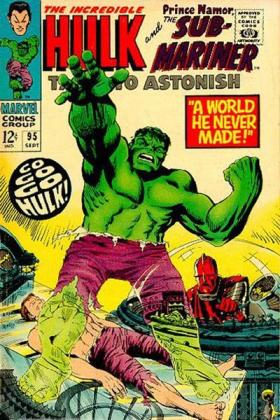

The crazy, absurdly ugly, without-a-real-world-purpose muscles of heroes and villains have another meaning: they embody the reader’s rage. In this way, Lee and Kirby’s Hulk is the ur-superhero: an openly monstrous hero-villain.

In fact, the heroic pose of the DCMV high-adventure Epic Hero is almost always monstrous. Bruce Banner, the Hulk’s alter ego, stands in for the nebbish reader, while the green monster is his unchained id. Like the Hulk, many heroes are enraged freaks: mouths screaming, eyes bulging, veins popping, bodies tensing as they ready themselves to exercise their rage-fueled power. Why are they always so angry?:

Speaking of exercise, how do they get these ridiculous bodies? Do they ever work out, or inject themselves with steroids? Why don’t we have story after story of heroes retiring early and dying because of the self-abuse they have endured? The answer: it’s fantasy.

Interestingly, the Hulk is a rare exception to the ban on exposed flesh: he wears almost no clothes. Readers accept his near-naked body because it’s not sexualized or objectified; it’s the existential anger of the misunderstood male who’s trapped in "a world he never made.”

If numerous attractive heroes with athletic bodies (e.g., Lee and Everett’s Daredevil) were to go nearly unclothed, the desires or anxieties of the hetero reader might be activated.

Also: The separation of the male pantheon into heroes and villains obscure that fact that both are Jekyll-Hyde-like doppelgangers of each other and the male reader. Male readers are likely to identify with villains who control women:

The often-maligned artist Rob Liefeld, a father of the Epic Body, understands all of this perhaps better than any other artist. He knows that it’s not about anatomy, proper proportions, or athletic bodies moving realistically. It’s about posing sexualized, over-muscled macho men. To emphasize this, he often eliminates panel backgrounds so that we focus solely on the hero. When Liefeld draws his trademark males with massive bodies and tiny heads, he’s onto something: heroes are not driven by mind or morality, but by fantasy bodies and sexual desires.

***

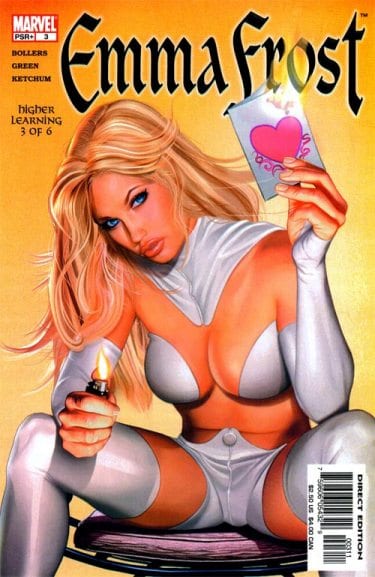

Those critical of gender politics in superhero comics claim that, while male costumes “make sense,” female outfits don’t. Their over-sexualized design is incompatible with crime-fighting: their huge breasts would pop out of the skimpy costumes. But in erotic power fantasies, the outfits make perfect sense—the possibility of a wardrobe malfunction is part of the thrill . . . Oops. As Kelly Thompson notes, many female heroes and villains look like actual porn stars.

And there’s a reason for this: the male reader wants a fantasy female he could theoretically “access” in real life. But he wants male heroes to be hyper-unrealistic—this way, he’s less likely to fantasize about them. If a male hero looked like a ripped male porn star, he could stimulate a reader’s homoerotic fantasy.

Critics often see the female body as exclusively sexual and the male body as merely physical. Yet in the eroticized DCMV, sex is power and power is sexualized. Thompson notes that Emma Frost has a “lingerie” costume that “makes sense” for her character, but not for other female heroes. Wouldn’t other women want the power to distract and seduce male villains, heroes, and readers?

In an ad campaign titled "The Real Power of the DC Universe," DC implicitly tried to answer accusations of sexism by showing the many heroic females that inhabit its comics. Yet the real power was revealed to be sexualized female bodies as drawn by male artists:

Readers claim that “the hidden phallus” is yet another sign that males are allowed to be free from sexualization. But in fantasies, the hidden and the repressed will out itself in some way. Male genitals are often implied by the costumes (in a way that female genitalia is not): bulges, covers, underwear-like tight briefs, etc. suggest that at any moment an “accidental” rip of the spandex might reveal a johnson . . . Oops.

[Note the lines emantating from the figure's "area." They have nothing to do with the costume; rather, they direct the reader to the symbolic home of the hero's power.]

And the prohibition against male genitalia is only a prohibition against the literal. Coded representations of exploding phallic power are everywhere, and have been a staple image for decades:

As always, Daniel Clowes, the premier theorist of the superhero, makes the logic clear in The Death-Ray:

One of Clowes’s influences, dirty joke scholar Gershon Legman, criticized the sadistic logic of popular culture’s attitudes toward sex. Since explicit displays are outlawed, libidinal energy is channeled into violence: we can’t make love, so we make war. The reader needs some kind of intense release—if he could get it watching sex, he wouldn’t need to get it viewing violence. In this way, the mainstream superhero story reveals itself as form of children’s literature that can’t deal with children’s and adult’s sexual urges. The absurd musculature of the Epic Super-Being announces that Thanatos has triumphed over Eros.

***

David Brothers writes that “a common problem for cape comics is . . . sexualized art. Imagery that prizes sexualization above all else—especially when it doesn't make sense for the story—can pull you out of the moment and stop your reading experience dead.” Brothers makes a distinction between plot and visuals that doesn’t work for me. As erotic power fantasies, these stories are fully loaded with sexual imagery.

I can’t separate the erotic images of male and female characters from the plot: both are crucial parts of these stories. It may be well done or poorly done, but either way, all the sexy poses and ugly muscles and tight costumes make perfect sense.

[To see a different approach to male heroes, I recommend Mark Waid’s current Daredevil (drawn by Paolo Rivera and others) as an athletic comic that resists the “epic hero, epic muscles” trend.]