In his instructional book Cartooning: Philosophy and Practice Ivan Brunetti writes, “I often think that, were my arms to be cut off in some tragic accident, I would still feel compelled to scrape my gums against the sidewalk in order to create a comic strip with my own blood.” (I can see one of these sidewalk comics now—square concrete panels with characters drawn in a bloody version of Brunetti’s affecting but unassuming geometry-meets-doodle style.) This “by any means necessary” commitment to creating comics is matched by his dedication to helping students grow into thoughtful artists. Cartooning is an intensive fifteen-week course that Brunetti developed in his years of teaching at Columbia College Chicago and the University of Chicago. This is not a book about how to draw funny pictures or write fantasy comics. It offers a methodical study of the organic and multidisciplinary process of cartooning.

In his instructional book Cartooning: Philosophy and Practice Ivan Brunetti writes, “I often think that, were my arms to be cut off in some tragic accident, I would still feel compelled to scrape my gums against the sidewalk in order to create a comic strip with my own blood.” (I can see one of these sidewalk comics now—square concrete panels with characters drawn in a bloody version of Brunetti’s affecting but unassuming geometry-meets-doodle style.) This “by any means necessary” commitment to creating comics is matched by his dedication to helping students grow into thoughtful artists. Cartooning is an intensive fifteen-week course that Brunetti developed in his years of teaching at Columbia College Chicago and the University of Chicago. This is not a book about how to draw funny pictures or write fantasy comics. It offers a methodical study of the organic and multidisciplinary process of cartooning.

Brunetti has released four issues of Schizo (#s1-3 are collected in Misery Loves Comedy), three collections of gag cartoons (Haw!, Hee!, and Ho!), and has edited the two-volume Anthology of Graphic Fiction, Cartoons, and True Stories. He is not only a skilled cartoonist, but also a stylish writer and careful comics theorist. Cartooning reflects on authenticity, self-awareness, and the peculiar nature of the art form, addressing readers in ways alternately amusing, self-deprecating, and—most importantly—challenging. Students will leave Brunetti’s course with a strong sense of what it takes to commit their vision to paper. All readers will take away from Cartooning a new understanding of what goes into making comics and a heightened appreciation of the medium.

[Black and white images come from Cartooning, color images from “Mr. Peach,” a recent Brunetti New Yorker strip about teaching.]

KEN PARILLE: I would certainly recommend this book to non-cartoonists since, as its subtitle makes clear, it’s also a philosophical tract about the medium—its forms, history, technical challenges—that anyone interested in cartoons and comics would find valuable. Did you have a dual audience of cartoonists and general readers in mind as you wrote it, or is this just a lucky accident?

IVAN BRUNETTI: My audience was basically anybody that would consider taking a course called “Cartooning.” As I've learned from my own teaching, I cannot predict who would be interested in such a course. I hope anyone and everyone would find something to enjoy. I was seeing my syllabus, which I had posted online, being unceremoniously stolen (sometimes verbatim) by others on the internet and even in print. I wanted to publish the book so that I could lay some claim to my own ideas before they became public property. Also, from what I saw, the instructors stealing the syllabus didn't really understand the syllabus or the reasoning behind it. While it's flattering that my structural ideas were accepted with such ease, as if they were the most natural way in the world to teach comics, as if they were accepted ideas blithely floating in the communal ether, I was a bit irked to find that I received zero credit. I'm a bit sensitive that way. In the book, I made a concerted effort to credit those from whom I was inspired. It's just common courtesy. Anyway, the book was a way to set the record straight, so to speak, and to explicate the syllabus and the structure of the course. I found it disconcerting that people were stealing bits and pieces of the syllabus, with only a superficial understanding of the purpose behind using, say, a one-panel gag or a four-panel strip. The book, I hope, makes clear that such fetishization of format simply will not do and is in fact antithetical to the spirit of the course. Anyway, any and all are welcome to read the book. I just hope it will have some value to somebody out there.

PARILLE: One of the most striking things about Cartooning is its selective use of illustrations. Most instructional books give students an abundance of models (often far too many), but you don’t.

BRUNETTI: As it says on the indicia page, the illustrations are meant to be as unobtrusive as the typesetting. I did not want to use drawings that were good enough to serve as some sort of model to emulate. The book repeatedly stresses that students should find their own style, gradually, though a series of insights to be gained from the exercises and assignments. So the last thing I wanted to do was to display specific examples of comics, lest they use those as some sort of gold standard. So I made my own drawings as simple (and hopefully invisible) as possible; my hope is that they are not even seen as drawings, just as very basic diagrams to explain things that I couldn't with words alone.

PARILLE: The course is very carefully structured, but many assignments leave plenty of room for spontaneity, randomness, and accident, such as the timed “doodle 25 favorite characters” exercise, as well as the one that employs chance; students mix and match captions and drawings they have created.

PARILLE: The course is very carefully structured, but many assignments leave plenty of room for spontaneity, randomness, and accident, such as the timed “doodle 25 favorite characters” exercise, as well as the one that employs chance; students mix and match captions and drawings they have created.

BRUNETTI: While the book is partially designed for “home use,” so that students can take the course on their own, I also wanted to keep things flexible for anyone who wanted to use it as a textbook. Obviously some things have to remain flexible (and have to be modified) to fit the classroom environment. I will leave that to the creativity of the individual instructors. I try to encourage spontaneity, improvisation and free-association when I'm teaching (for the students and for myself). The important thing is to stay true to the spirit of the exercises, if not the letter.

PARILLE: You also avoid all of the “This is the proper way to draw a human body” or “Here’s how to draw a funny nose” type of tips, as you might find in other cartooning books.

BRUNETTI: There are plenty of books on those subjects, and I am no expert in either of those topics.

PARILLE: Which parts of the syllabus do you feel are most eye-opening for your students—which exercise, for example, most challenges their preconceptions about cartooning?

BRUNETTI: I find that students are often resistant to the first three weeks of class, questioning what the point or value is of the exercises and assignments. But the turning point tends to come between the third and fourth week, when the students produce a Kochalka-esque sketchbook diary for one week. They either embrace this assignment, or kind of get lazy and blow it. Many surprise themselves with their ability to keep up a daily strip, and really see (and push) their abilities. I can tell how a student will do in the class based on this assignment; it's like a microcosm of the course. Some people do really great stuff. It's been gratifying to see my students (and readers of the book) continue the assignment beyond the one-week period. I have one student right now who decided to take it upon himself to do the assignment for one year. He's on month number 8, and I can see his skill improving by leaps and bounds. It also forced him to expand his idea of storytelling, because it's hard to come up with something new every day; you have to let your mind wander and accept a lot of small moments as having their own narrative power. Cartooning takes a dogged determination, and this assignment really tests one's mettle.

PARILLE: Are there fundamental mistakes that you believe cartooning books or classes typically make?

BRUNETTI: Getting too caught up in technical stuff right off the bat. I think it's best to develop narrative skills early on, and also to encourage an open atmosphere in the classroom, where the students can feel OK about exploring any topic they wish. That's why the “tools” chapter and its corollary, the “style” chapter, are smack dab in the middle of the course, not the beginning.

PARILLE: In Cartooning, as in the volumes of your Yale Anthology of Graphic Fiction, you move from basic to elaborate cartooning forms.

BRUNETTI: As much as students are often impatient, I can't see any other way of going about teaching. How does one start with something advanced? One needs the building blocks of the simple. Now, I think how I define “simple” and “complex” (which to me, is in terms of compositional structure), is not typical and thus sets the book apart from others. One student (a college senior) recently told me of his struggles in freshman year, taking Drawing I: “The teacher kept going on and on about The Line, and what it is, but at that age, you just want someone to show you how to draw something cool, like fire!” Anyway, he now knows better. As a teacher you have to keep in mind that the students have to eat their spinach first, and the dessert comes much later.

PARILLE: Are there assignments you tried but didn’t work out as you hoped, and so don’t appear in the final syllabus?

BRUNETTI: Many, many, many, many examples. One was the “Worst. Comic. Ever.” in-class exercise, which then turned into a take-home assignment, and which actually did not work at all. I like the idea of doing an exercise, and then as an experiment, seeing if you could “make it worse.” It really gets you to look at your artwork (or story) in a different light, and you start to see it for what it is (by examining what it is not). But the assignment never caught on with the students (I can think of only two examples where someone did something interesting with it). They moaned and groaned and decided “make it real sloppy” was the only way to make something “worse.” In the end, I converted it to a “thought exercise” and simply listed it as a suggestion in preparation for creating the final project (see the chapter on Weeks 11-14).

PARILLE: You say that originality is not a goal, though the course encourages a very thorough self-awareness on the part of students, one that would likely lead them to develop a far less derivative style than they might have developed, had they not taken your course.

BRUNETTI: To be exact, I say that originality is not something to strain for. I quote Marcella Hazan, who says that it should not be an explicit goal, but it can certainly be a consequence of your intuitions. The book is all about developing those intuitions. Originality will arise, naturally, from doing the exercises and assignments and paying attention to one's own process.

PARILLE: Cartooning is dedicated “to all of [your] students, past and present. Even the bad ones.” This makes me curious about how you think about the thorny question of “talent.” Do you think of it as “people either have it or they don’t?” Or is the idea of talent irrelevant to your beliefs about a student’s success and/or the way you structure the course’s syllabus?

BRUNETTI: To me, art is not about talent, it's about hard work. It's about developing one's intelligence, thoughtfulness, and sensitivity. To some degree, the potential for these things seems to vary, implying they are perhaps innate, but I think anything can be nurtured (or neglected). Something might not come easy, but it can be learned. It's matter of will, desire, determination, and hard work. How much is it worth to you? The definition of what is considered “talent” or “skill” keeps changing. I say if one develops him or herself as a human being, then art can follow. If no adequate form exists, the artist will create a new one.

PARILLE: Have you seen students develop over the 15-week course in ways that you wouldn’t have predicted based on their work in the opening weeks?

BRUNETTI: As mentioned above, the one-week diary (homework for week 3) really seems to be a telling microcosm of the course. This is where students can surprise me (for good or ill). The 8th week is also an interesting one, where they copy another artist's page. Sometimes students that cannot draw very well (technically speaking) come up with amazing stuff, like a weird hybrid of themselves and what they are copying. I try to have them develop the stuff that looks like the “mistakes.”

PARILLE: Your main concern seems to be that a student be honest in her approach to the assignments.

BRUNETTI: I hadn't thought about that. I don't know if I had a main concern, other than making sure the students push themselves to do their absolute best. But I would agree that nothing good can come out of dishonesty, so having an honest approach isn't a bad place to start.

PARILLE: You write that “cartooning is primarily verbal,” which I find interesting. Most people say the opposite, that cartooning is essentially a visual medium or practice. Could you talk a little about what you mean by “primarily verbal” and about how this idea informed your development of the syllabus?

BRUNETTI: Let me clarify that: I say that for me cartooning is primarily verbal, a process of translation, based on my own personal history of having to learn another language and having to learn to interpret (translate) the world visually despite my faulty eyesight, as I describe in the book's introduction. But I also mention I don't want to saddle anyone with the travails of my own personal history, so I try not to belabor the point about this verbal interpretation, and I quickly move on to cooking a pot of spaghetti, which is a metaphor anyone can relate to, I hope. Mostly I am trying to say that one has to be aware of one's own process, and learn to value and maximize that process (this will differ from person to person, and the introduction merely describes my own plight). This stuff informed my development of the syllabus insofar as the whole book can be seen as a self-help book with the author as its primary (perhaps sole) audience. In all seriousness, I try to blend the visual and verbal through the book, so that they “fuse” for the student as one organic process. Sometimes the verbal part gets short shrift, so I don't mind emphasizing it.

PARILLE: In “Mr. Peach,” a recent strip of yours in the New Yorker, a student asks the teacher if he can use the computer to complete a comics assignment. In your course, you initially don’t allow students to draw on a tablet or use a computer for lettering, even if they create a font of their own handwriting. How does the computer get in the way at the learning stage?

PARILLE: In “Mr. Peach,” a recent strip of yours in the New Yorker, a student asks the teacher if he can use the computer to complete a comics assignment. In your course, you initially don’t allow students to draw on a tablet or use a computer for lettering, even if they create a font of their own handwriting. How does the computer get in the way at the learning stage?

BRUNETTI: In the book, I do let the students use whatever tools they wish for the final project, and over the years I have “lightened up” in the classroom and thus am OK with computers throughout the course (if they are used intelligently and creatively). Since I don't have the luxury of looking over the students' shoulders in the book, I had to err on the side of caution. I'll explain my reservation about relying on computers too much: I don't like the idea of everyone force-feeding their artwork into software that will mathematically interpolate the data and spew out a sort of “samey” result. Why limit yourself that way, right off the bat? I think it's better to figure out a way to get the computer to bring out what is unique and idiosyncratic in your artwork, not to standardize it toward some vague “professional” standard.

PARILLE: In the same strip, a student asks if he can use non-standard panel shapes in his work. In Cartooning, and in your own work, you emphasize square/rectangular panels with unbroken borders.

BRUNETTI: I'm not against any particular panel shape, but in that comic strip I meant to show that no one was actually listening to a word I said, and that the students could not care less about my admittedly abstract concerns. It is also implied that perhaps the students are right. Having said that, diagonal panels rarely work, at least at the student level. Just an observation from my own experience.

PARILLE: You take a strong stance against student collaboration in the exercises during the course. What’s your rationale for this—have students often wanted to divide labor, i.e., one scripts, another draws?

BRUNETTI: The book is about “fusing” writing and drawing. I use the metaphor of an emulsion. Well, an assembly line approach takes the salad dressing and separates the oil and vinegar from each other all over again (but both have been degraded in the process). I am not against collaborations, as there have been many great collaborations, but as I state in the book, even if one wishes to work in an assembly-line system, it is still good for the writer to know what the artist will have to do, and vice versa. My book is not only about fusing the two, but also being sensitive to both parts of the process that you are fusing. I have had students in the past wanting to write scripts, although I no longer have this issue, as I now teach at an art school exclusively. Everyone wants to draw. (Getting them to write something interesting is more the challenge now.)

PARILLE: If you were to develop a Cartooning, Part Two—a follow-up 15 week course—what kinds of exercises would you include and what would be some general goals for the course?

BRUNETTI: I do teach a related course, Drawing the Graphic Novel, and I do have a series of exercises and assignments totally separate from the ones in Cartooning. I'm still sharpening this course, and experimenting with the content. It's slowly turning into an interesting variation on the Cartooning book, and it's structurally very different. It's more about making booklets and books. Seeing as I've had bad luck when I've shared this kind of information in the past, I don't feel comfortable giving my ideas away. Maybe I'll do another book someday. My goal: make the new course a sibling to Cartooning.

PARILLE: Has developing Cartooning’s syllabus and teaching it affected your own cartooning in any specific ways?

BRUNETTI: I think about what I'm doing a lot more than I did when I first started; that's not always good, because I tend to over-think things. I tend to base my exercises and assignments on what I'm working on at any given point (I don't only teach comics, I should mention), so it's more of a case of my work influencing my teaching, as opposed to the other way around. But I have been inspired at times by the amazing work some of my students are doing. I fully expect more and more of them to be working cartoonists in the future. I teach full-time now: it is my job, my livelihood, my vocation. The demands of teaching are greater than every job I've ever had. I have no training in this, and so it's been a tough transition. I probably draw less now than at any other point in my life. This has been the source of great sadness, but I am slowly coming back to drawing my own comics. Hopefully, at some point I achieve some balance. I miss drawing stories and have much I have left unsaid in that regard. I'd like to say it before arthritis cripples me, I get run over by a bus, civilization collapses, or I die of cancer, whichever comes first.

PARILLE: There’s a fascinating moment in Cartooning when you’re creating a single-panel comic about Holden Caulfield—an attempt to capture the essence of that character. You list literally dozens of questions that you ask yourself before you begin and while you are working on the cartoon. How closely does this series of questions approximate your actual thinking process as you draw your own work?

BRUNETTI: It's pretty much almost a direct transcription of my thought process. I'm a slow typist, but it gets close.

PARILLE: What are you working on now?

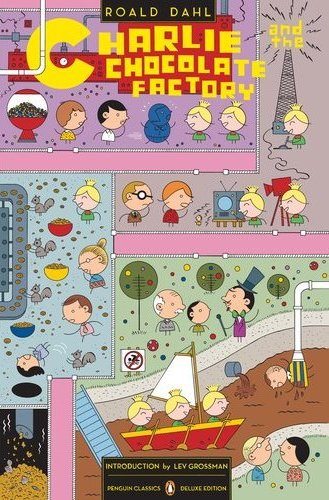

BRUNETTI: I just finished drawing the cover of Roald Dahl's Charlie and the Chocolate Factory for Penguin Classics Deluxe Editions; it's a great honor to be a part of this series. I drew a couple of comic strips that have appeared in the New Yorker this year, and I hope to submit more work to them soon. I plan on using the summer to work on a long-delayed graphic novel (ugh, I hate that term); we'll see how that goes. I actually have two long stories in mind, and I figured as long as I start one of them, I'm in business.